Local History - part 1

Witham on the Hill's early history

- The village is first mentioned in the Domesday Book in 1086, confirming its long history.

- The name "Witham" comes from the Anglo-Saxon words "wīg" (a willow) and "ham" (a homestead or village), indicating it was a village by a willow tree.

- Historically, Witham-on-the-Hill has been a settlement with a rich past, dating back to the Anglo-Saxon period.

Medieval and later periods

- The village is home to a set of medieval stocks and whipping post, now protected by a tiled canopy, which were used to punish minor offenders.

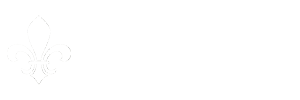

- The parish church, St. Andrew's, dates back to the 15th century, with its spire rebuilt in 1738.

- In 1750, Witham Hall was erected, and it was the seat of the lord of the manor, Major General William Augustus Johnson, in 1841.

Modern history

- A major fire in 1775 destroyed the inn, vicarage, and other buildings.

- In 1857, the current Parish Hall was built as a village school.

- The Six Bells Pub was built in 1905 and is now a Grade II listed building.

- In 1959, Witham Hall was purchased and converted into a preparatory school, which remains operational today.

- In 2002, GM rapeseed trials were conducted at West Farm

Geography

The village is between the east and west tributaries of the River Glen, and despite its name, is not on the top of its 'hill', which reaches a peak 1 mile (1.6 km) west towards Careby. It is approximately 0.5 miles (0.8 km) from the A6121 Bourne-Stamford road. To the west is Little Bytham, and to the east are Manthorpe and Toft. The predominant landowner in the area is the Grimsthorpe Estate.

The civil parish covers a large area, extending north into Grimsthorpe Park and Dobbins Wood where it meets the boundary of Edenham, and the boundary with Toft with Lound and Manthorpe is mostly along the A6121. Manthorpe were once part of the civil parish.

Contents

Local History -These historical articles are reproduced in this compilation with the kind permission of their author, Dick Mundy of Manthorpe. |

||

| The Old Radio Station Swallow Hill | The Earl of Lindsey | Saxon Architecture |

| The Mallard | Recumbent Effigies | Woodcroft Castle |

| A Great Treasure from a Small Village | Castle Bytham | Lost Villages |

| Grimsthorpe Castle | The Flodden Plaque | Hereward the Wake |

| Baptist Noel | Clipsham Yew Tree Avenue | The Essendine Earthworks |

| The Siege of Burghley House | Car Dyke | The Manners Monument or a Mystery at Uffington |

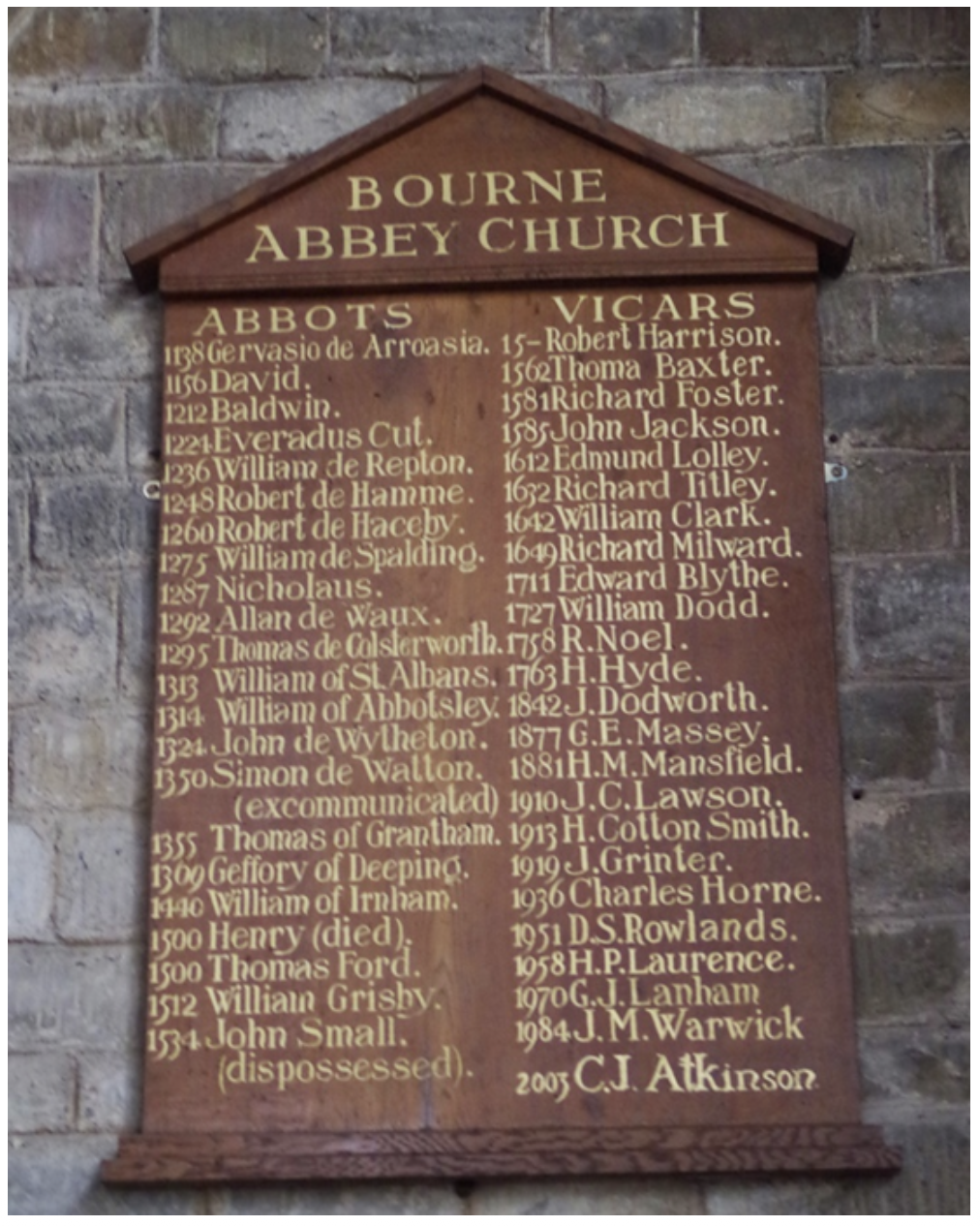

| Bourne Abbey | Kate’s Bridge | The Toft Trig Point |

| The Fen Causeway | Bowland’s Gibbet | Registers of Vicars |

The Old Radio Station - Swallow Hill

One place that has always intrigued me on my travels is the now derelict radio station on top of Swallow Hill on the left of the road leading from Manthorpe into Thurlby. The station is in fact just inside Manthorpe parish. The boundary between Manthorpe and Thurlby goes along the road past the radio station and then turns left to follow the hedge line northwards on the Thurlby side, with the radio station in the corner. For those of us with a passion for maps, the parish boundary and the station are marked on the Ordnance Survey Explorer map sheet 248 (Bourne) at grid reference TF 0816. The station consists of a small brick building with a notice on the door announcing that it is “British Gas East Midlands Thurlby Radio Station”. A large concrete slab is to the right. The aerial mast must have been at least 100 feet tall and was built in the centre of the slab with guy ropes anchored at each corner. The whole site is surrounded by a wooden fence, with a gate in front of the building. Some years ago, when I was younger and fitter, I was very keen on archery. When driving home from my place of employment in Peterborough, I used to gauge the strength of the wind by the amount of bending in the mast. This told me whether or not it was too windy to go shooting. At least ten years ago the mast disappeared and the whole site was abandoned. It has now been taken over by trees, which have grown so 1well that the building has almost been consumed by them. Some parts of the fence and the gate have collapsed. It is in a pretty poor state. There appears to be a lack of information about the radio station and why it has been left in this way. Reference books and local histories offer no clues. Despite diligent searching, the only mention I can find on the internet is a photograph on the geograph.org.uk website dated 2006 which shows the radio station and aerial mast at the above grid reference. As a keen photographer I have often taken pictures of the station showing its gradual decline. The earliest is from 2011, probably not long after the mast was dismantled, and before all the foliage took over. Derelict buildings such as this are usually sold off, snapped up by developers and the site covered with expensive housing. But strangely this has not happened to the radio station. Back to top

The Earl of Lindsey

Tucked away at the east end of the north aisle of Edenham Church is a very fine monument to the first Earl of Lindsey. Born Robert Bertie in 1582, he became the 14th Baron Willoughby d’Eresby in 1601 and was created Earl in 1626. His home was Grimsthorpe Castle, granted by the Crown to the d’Eresby family in 1516. The Earl was killed on 23rd October 1642 at the battle of Edgehill, the first major action of the English Civil War, the armed conflict between King Charles I and Parliament. The Earl of Lindsey was an experienced soldier who had fought in Spain, the Low Countries and at sea. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he and his son Montague raised regiments in Lincolnshire for the King. In August 1642, at the age of sixty, Lindsey was appointed Lord General of the main Royalist army. When the King’s nephew, Prince Rupert of the Rhine, was appointed commander of the Royalist cavalry, he would only take orders from the King himself.

This placed Lindsey in a very difficult position and led to bitter acrimony. At the council of war before the battle of Edgehill, Lindsey quarrelled with Rupert over the deployment of troops. When the King followed Rupert’s advice, Lindsey angrily resigned his post and was promptly replaced as Lord General. Lindsey then fought on foot as a colonel at the head of the Lincolnshire infantry regiment that he had raised. His son, commanding a troop of cavalry under Rupert, dismounted and stood by his father's side. Family loyalty came before military discipline. During the battle, Parliamentary horsemen violently attacked the Royalist infantry division. The Earl of Lindsey was shot in the thigh, then he and his son were captured. Lindsey was carried to a nearby barn, where he died from his wounds on the following day. The King had been shaken by the suffering he had witnessed. Lindsey’s fate was still unknown. The King sent a herald to the Parliamentarian lines offering free pardon to all the rebels. The herald brought back to the royal camp the news that Lindsey had died. It was the only positive result of his mission. King Charles was eventually defeated in the Civil War and was tried and beheaded in 1649 on the orders of Oliver Cromwell leading a Puritan faction in Parliament. Lindsey’s son Montague was one of only four peers brave enough to attend the King’s funeral at Windsor. After more fighting, a failed attempt by Parliament to establish a republic, and the death of Cromwell in 1658, the monarchy was restored with Charles II, son of Charles I, as King. At Edenham there is an array of monuments in the church to the Willoughby d’Eresby family. The text of the monument to the first Earl of Lindsey and his son Montague is in Latin and for us non-scholars a helpful translation is affixed. A fitting memorial to a brave man who had the courage of his convictions but paid the ultimate price. Back to top

Saxon Architecture

One of the attractions of this part of England is the variety and number of parish churches. All history is there. Churches record the story of the parish, contain monuments to local worthies, and parts of the building often date back a thousand years to Saxon times. The Anglo-Saxons arrived in England after the Romans left in about 400 AD and governed the country until conquered by the Normans in 1066. During that time, they fought ferociously among themselves and were frequently invaded by the Vikings from Denmark. Because secular Saxon buildings were constructed of wood with wattle and daub walls, such depredations left none of these inflammable structures standing. Only their monasteries and churches were built in stone. There are good examples in the north of England at Escomb, County Durham and the monastic buildings at Monkwearmouth and Jarrow. An early Saxon church of note is at Brixworth, Northamptonshire, partly built of old Roman bricks. At nearly 100 feet long, Brixworth is large compared to other early Saxon churches. Churches tend to develop over time and often display many different periods of architecture in one building. In our area there are quite a few displaying Anglo-Saxon origins. Arguably the finest is St. John the Baptist at Barnack near Peterborough (pictured).

The oldest parts of the church are the two lower stages of the tower which date from 1000 to 1020 in the late Saxon period. There are particularly fine and unusual carvings on all its faces as well as typically Saxon windows and the south doorway. St. Mary Magdalene at Essendine has a useful architectural description of the church on an information board inside the building, which dates the south doorway to the first half of the 11th century. The arch has a Norman zig-zag decoration and contains a particular device used frequently by Anglo-Saxon church builders. St. Medard in Little Bytham is supposed to have Saxon quoins (corners) to the nave but on a recent visit I could not spot them. St. Peter and St. Paul in Market Overton in Rutland was originally 10th century Saxon of which only the tower arch remains. It is said to be the only notable piece of Anglo-Saxon architecture left in that county. At St. Michael and All Angels at Edenham there is a small but very fine array of Anglo-Saxon remains. High up on the wall of the south aisle are two 8th century carved roundels, indicating that this was probably the original external wall of an ancient Anglo-Saxon minster. The shaft of an Anglo-Saxon cross of the same period is displayed at the north west of the nave. A rare pre-Viking sculpture from the late 8th century decorated on all four sides sits at the west end. A useful typed notice tells the visitor that their presence indicates pre-Conquest Christian worship at Edenham. This is history you can visit, look at and touch. Walk around the church, admire the architecture and monuments, make a small monetary contribution and say a prayer if you will. Or at least we could until this tiny virus fouled up our lives. Roll on the time when the bug is defeated and we can get back to near normal and appreciate these wonderful buildings. Back to top

The Mallard

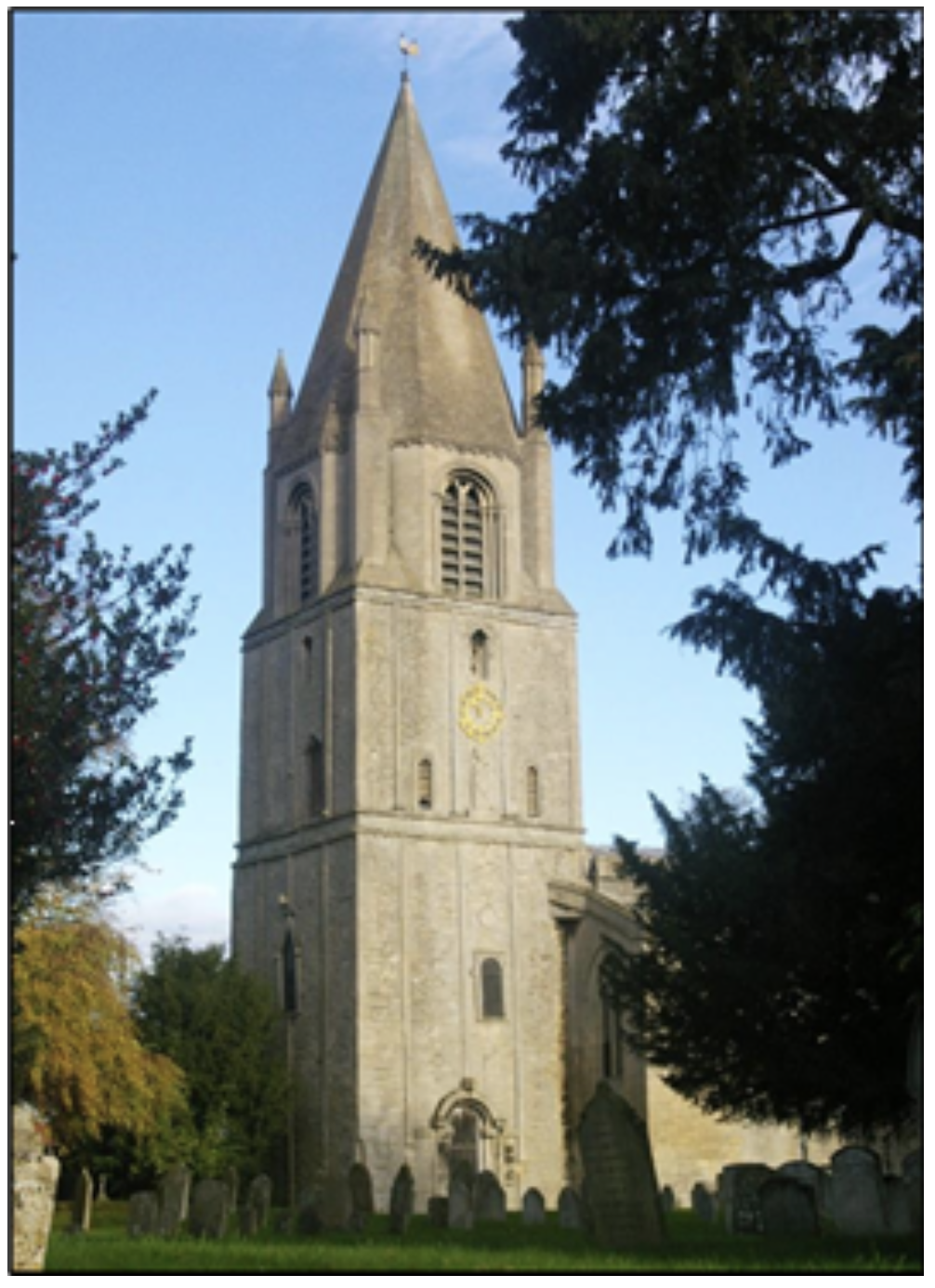

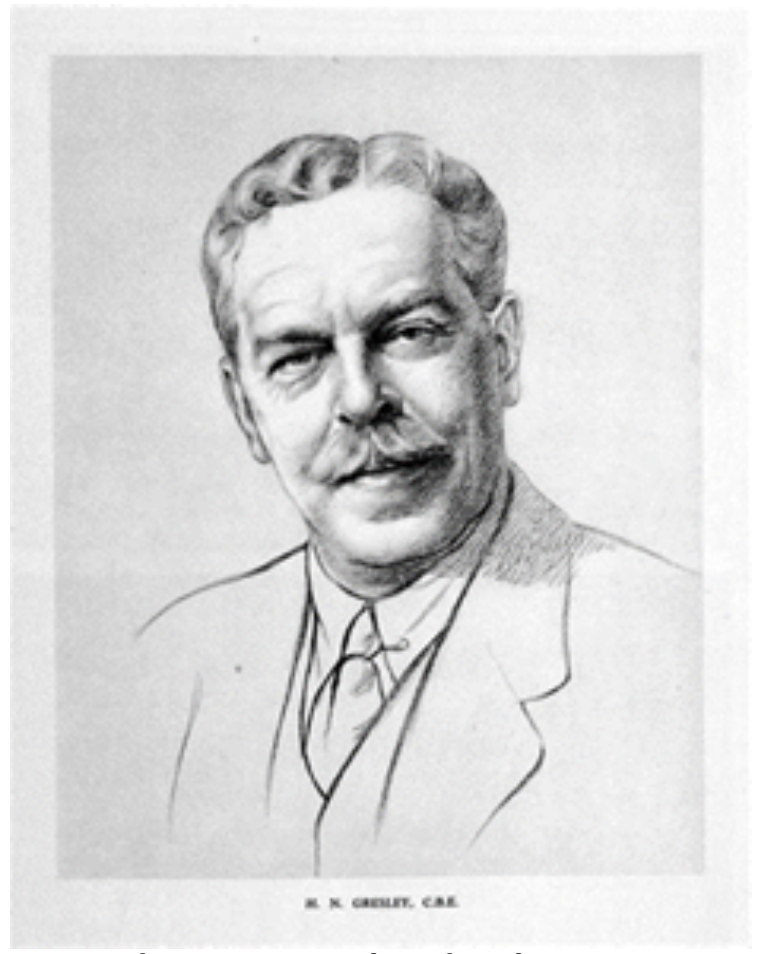

Just beyond the boundary of our group of parishes, a record was set over eighty years ago which still stands today. The world speed record for steam locomotives at 125.88 mph was achieved on 3rd July 1938 on the East Coast Main Line. The exact spot is between Aunby and Carlby, at milepost 90¼ on the up line towards London. The record was obtained by No. 4468 Mallard, a Class A4 locomotive, designed by Sir Nigel Gresley, chief engineer of the London and North Eastern Railway.

Mallard and its tender, painted in garter blue, was pulling seven carriages weighing in all 240 tons. The attempt was rather hush-hush, it was made on a Sunday, under the pretext of a trial of a new quick-acting brake, and no fare-paying passengers were carried. Crewed by driver Joe Duddington and fireman Tommy Bray, Mallard’s streamlined design and some clever engineering powered it to the record. The train rocked so violently that dining car crockery smashed, and red-hot bullet-like cinders from the locomotive broke windows at Little Bytham.  Mallard’s big-end bearings were running so hot that it had to slow down considerably to avoid them melting. In fact, Mallard had to 7be detached from the train at Peterborough for repairs and the journey back to King’s Cross continued with a standby engine. Mallard retired from regular service in 1963 after covering almost 1.5 million miles, was fully restored to working order in the 1980s, and is now preserved at the National Railway Museum in York. Sir Nigel Gresley was born in 1876, knighted in 1936 and died in 1941. He was responsible for designing many famous steam locomotives including The Flying Scotsman. The Gresley Society was founded in 1963 to commemorate the work of the great man. On 29th July 1998 the society installed a large sign beside the East Coast Main Line to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the event.

Mallard’s big-end bearings were running so hot that it had to slow down considerably to avoid them melting. In fact, Mallard had to 7be detached from the train at Peterborough for repairs and the journey back to King’s Cross continued with a standby engine. Mallard retired from regular service in 1963 after covering almost 1.5 million miles, was fully restored to working order in the 1980s, and is now preserved at the National Railway Museum in York. Sir Nigel Gresley was born in 1876, knighted in 1936 and died in 1941. He was responsible for designing many famous steam locomotives including The Flying Scotsman. The Gresley Society was founded in 1963 to commemorate the work of the great man. On 29th July 1998 the society installed a large sign beside the East Coast Main Line to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the event.  It is sited at the precise point where the highest speed was reached. The cost was funded partly by the society, by individuals and railway companies. The Mallard sign can be seen either by buying a railway ticket, and hoping that the train will not be going too fast, or from the B1176 going from Ryhall towards Little Bytham. Past the turn off to Carlby, the road ascends to Barbers Hill and at the top just past the farm house on the right is a gated field entrance from which the sign can be viewed. Parking is risky. Either on the narrow verge, or at the field entrance, or another on the left slightly further on. However, the sign is a long way from the road. You will need: clear weather, good eyesight, good binoculars, and a telephoto lens for photography. The railway authorities, or possibly the landowner, have very helpfully cut back the tree growth allowing a better view of the sign from the road. All this is old news to railway enthusiasts, among whom I do not include myself. Back to top

It is sited at the precise point where the highest speed was reached. The cost was funded partly by the society, by individuals and railway companies. The Mallard sign can be seen either by buying a railway ticket, and hoping that the train will not be going too fast, or from the B1176 going from Ryhall towards Little Bytham. Past the turn off to Carlby, the road ascends to Barbers Hill and at the top just past the farm house on the right is a gated field entrance from which the sign can be viewed. Parking is risky. Either on the narrow verge, or at the field entrance, or another on the left slightly further on. However, the sign is a long way from the road. You will need: clear weather, good eyesight, good binoculars, and a telephoto lens for photography. The railway authorities, or possibly the landowner, have very helpfully cut back the tree growth allowing a better view of the sign from the road. All this is old news to railway enthusiasts, among whom I do not include myself. Back to top

Recumbent Effigies

This splendid term refers to a type of English church monument in the form of a life size figure lying down, carved from stone or wood, sometimes covered in painted brass, and mounted on a stone plinth or chest tomb. There are a surprising number of these effigies in our local parish churches. The figure can be a knight in armour from the late 13th or early 14th centuries. Good examples are at Burton-le-Coggles, Swinstead, Uffington and Wilsthorpe. Sometimes the effigies are in pairs with a lady lying next to her husband. These are found at Stoke Rochford, Careby and Edenham. When recumbent effigies were raised onto chest tombs, they were far more elaborate than those lower down, and are from later centuries. There are some very fine recumbent effigies of this type in Rutland. At Brooke, the monument to Charles Noel who died in 1619 aged 28 is an alabaster figure in plate armour with panel and crest above. At Exton, one chest tomb bears recumbent effigies of John Harrington (died 1524) in full armour with his wife Alice beside him. Another is to Anne, Lady Bruce of Kinloss (died 1627). Her tomb is made from black and white marble and is of great importance and exceptional beauty according to “Buildings of England” by Pevsner. They must have been very wealthy in Rutland!

All the foregoing refers to monuments of the nobility and landowning classes who had the wealth and social standing to have elaborate tombs inside the church. The closer the tomb is to the altar, the greater the prestige of the family. The poorer people and lower social classes had to make do with being buried outside the church in a simple grave. Crossed legs on a knight effigy indicate that he served in the crusades, or had taken crusading vows. The vow was referred to as “taking the cross”, hence crossed legs. A good example is at Swinstead (pictured). When the feet rested on a lion, it indicated valour and nobility for men. When on a dog this shows loyalty, often used for ladies. Sometimes the feet rested on a heraldic beast from the family coat of arms. Military historians have found that some knight effigies are carved so well that they give valuable information on styles of armour in medieval times. Some of these effigies are badly weathered, perhaps because they have spent centuries outside the church. Now and again one or both feet are missing. These signs indicate wanton damage by Protestants during the Reformation or by Parliamentarian troops in the Civil War. At Edenham, effigies were thrown out of the church at the Reformation and only brought back inside at the start of the 20th century. At Wilsthorpe and Burton-le-Coggles feet are missing. As for identification of the deceased represented by the effigy, the best place to find out is on a plaque or helpful notice in the church itself, or the guidebook often written by a scholarly clergyman in years gone by. So next time we are allowed out to visit a church, look around for recumbent effigies, make a contribution, dig deep and buy the guidebook, and enjoy the history. Back to top

Woodcroft Castle

Woodcroft Castle is a mainly late 13th century structure with a few early Tudor period additions, tucked away in the back roads just north of Peterborough. It was the site of the only substantial military action of the English Civil War in Peterborough, when in 1648 it was besieged by Parliamentary forces determined to capture Michael Hudson, its commander. Dr. Hudson was a priest, chaplain to Charles I, and, despite his calling, a dyed-in-the-wool Royalist who launched armed raids into the surrounding area. The siege was a bloody affair which led to deaths on both sides, including Dr. Hudson, but victory for the Roundheads. I only found out about the castle in the summer of 2019 in an estate agent’s advert in an old newspaper. I did a bit of research and it seemed a fascinating place. So even though privately owned, I was keen to visit. The castle is not easy to get to. I tried the narrow lane south of Etton from the Glinton to Helpston road but was thwarted when I reached the level crossing of the East Coast Main railway line. The lady crossing keeper warned me that as it was only an insignificant crossing, controlled from Helpston, it could be a half hour wait until the gate was opened. I had better luck with my next attempt. I drove south along King Street and left to Marholm. In the village I turned left along the narrow lane back to Etton. After 2 miles I reached Woodcroft Castle and parked on a muddy farm track opposite. The castle is circled by a moat and well set back from the road in extensive grounds with large trees. I walked up the entrance drive, hoping to meet someone who would give me permission to take photographs. A gang of builders was renovating the castle and they had their vans, cranes, sacks of cement and various bits of equipment strewn about in front of the building, somewhat spoiling the view. I enquired of who appeared to be the head man, who said I should speak to the owner. One of the builders then disappeared into the castle. I followed him and the owner appeared, an American gentleman. I asked for permission to photograph but he was reluctant at first, mentioning rightly that the castle was not looking its best and did not want any images posted on social media. I gave him my solemn word that any pictures would be solely for my private use and guaranteed that they would never appear in public. (That is why I cannot provide any photographs). He graciously accepted my assurance and gave me permission. The foreman builder was a knowledgeable man, who told me that the castle dates from the 1200s and pointed out that the battlements along the frontage were more recent. He showed me the line on the central tower of an old pitched roof, saying that a flat roof was now concealed behind the parapet. On leaving I politely declined his request for a portrait and thanked him for all his kind help. A truly worthwhile expedition. Pity the castle was not open to the public. I mentally forgave the owner for entrusting a historic English structure to American hands. One could take the view that at least he was restoring the castle, which otherwise might have fallen into wrack and ruin. Back to top

A Great Treasure from a Small Village

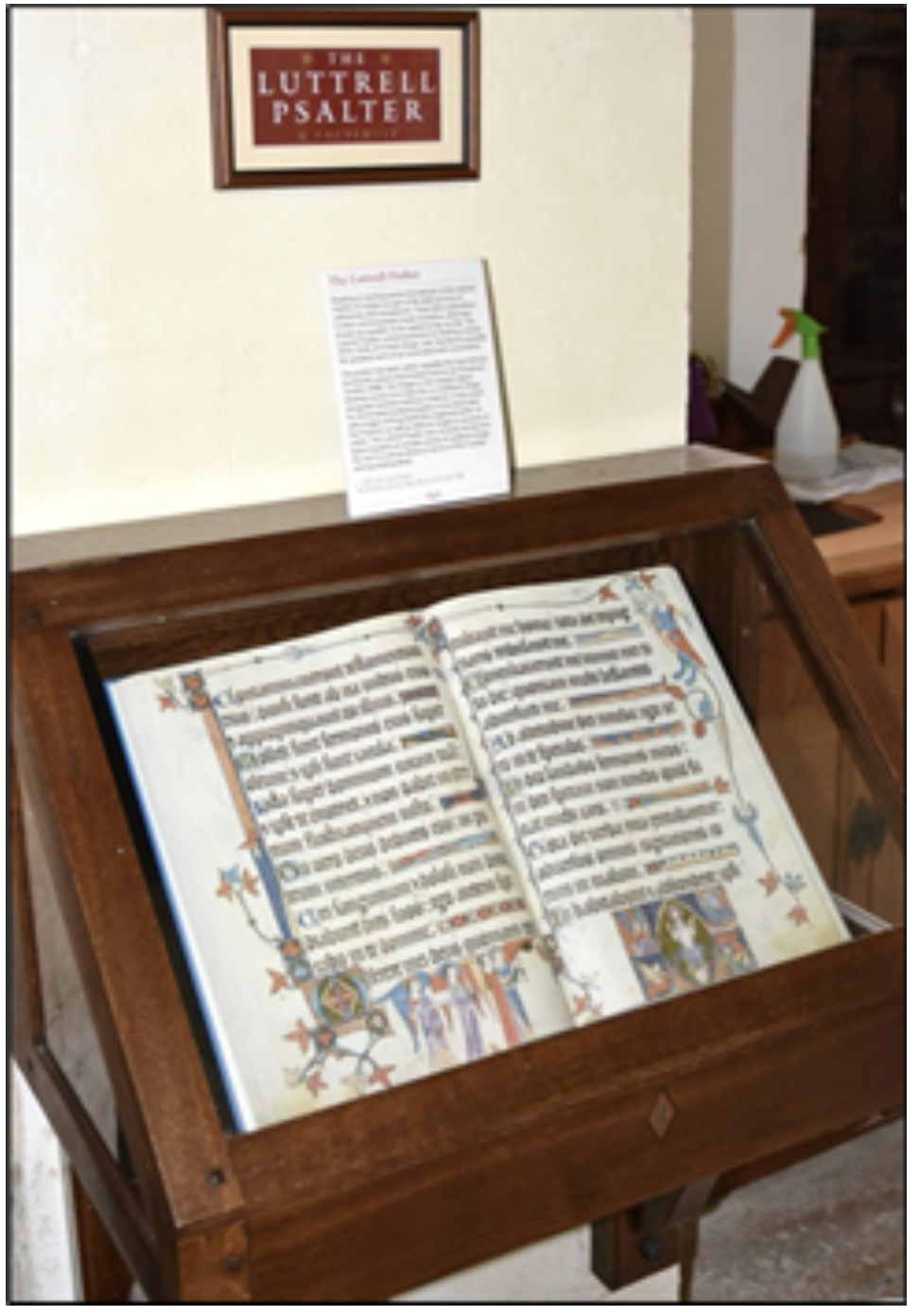

It is a surprising fact that one of the greatest medieval treasures of England originated in Irnham, a small village tucked away in the back roads north-west of Bourne. I refer to The Luttrell Psalter, a beautifully illuminated 14th century manuscript, the finest work of art to come out of Lincolnshire and which is ranked nationally alongside the Domesday Book and Magna Carta. A psalter is a book of psalms, about 150 ancient songs that appear in their own chapter in the Old Testament, but are often in a book of their own accompanied by prayers and a calendar of church feast days.

Many people learnt to read using a psalter. From medieval times to the present day, the psalms form a fundamental part of Christian worship for laymen and ecclesiastics alike. But the Luttrell Psalter is not just a religious work. It is famed for its rich illustrations of everyday rural life in the 14th century, exceptional in their number and in fascinating detail. There are lively, sometimes risqué, and often humorous scenes of corn being cut, a woman feeding chickens, food being cooked and eaten, portrayals of wrestlers, hawkers, dancers, musicians, an archery tournament, a mock bishop, scary monsters, and a wife beating her husband! The Luttrell Psalter was commissioned by Sir Geoffrey Luttrell (1276 – 1345), Lord of the Manor of Irnham. It was illuminated and written in Latin on vellum from about 1320 and took ten years to complete. Art historians have confirmed that the style of the illumination points to this date. Sir Geoffrey was a rich man. He owned the village and the manor house, Irnham Hall, near the parish church of St. Andrew’s. As well as Irnham he held estates across England thanks to a distant ancestor who shrewdly married a wealthy heiress and whose loyal service to King John had been rewarded by numerous land grants. Sir Geoffrey was summoned for military service by Kings Edward I and II and fought in the Scottish wars between 1297 and 1319. Following on from a property dispute, he conducted a private war with a neighbour, one Roger de Birthorpe, against the monks of Sempringham Priory, although only de Birthorpe was censured. Sir Geoffrey was supposedly buried in St. Andrew’s churchyard. The Psalter contains his portrait, fully armed and mounted on a warhorse. Various historians and scholars state with confidence that because Irnham is a tiny village there is no way the Psalter was produced there, and the work was certainly created in Lincoln by scribes who remain unknown. On a recent visit to Irnham, I met a local man who disputed this claim and said that the scribes may have come from Lincoln, and some work may have been done there, but it was almost certain that the Psalter was produced in Irnham. He told me that the original is in the British Library in London and is one of their top ten treasures. A facsimile copy is kept in the local church in a locked glass case for all to see (pictured). My informer praised the illustrations of medieval village life in the 14th century in the margins of pages in the Psalter. Not in towns and cities like York or Lincoln but in small villages like Irnham. There is a cutting from a newspaper dated 2006 in the church porch which mentions the publication of the British Library facsimile edition at a price of £295. A well-known second-hand book website now lists used editions at prices above £1400. Before the British Library was a separate institution, all its works were held in the British Museum. It was this body who tried to buy the Luttrell Psalter in 1929 from Mary Angela Noyes, wife of the poet Alfred Noyes. But at the time could not afford the then record asking price of 30,000 guineas (£31, 500). An anonymous benefactor stepped in and loaned the money to the museum, interest free. The benefactor was later revealed as the American banker and millionaire J. P. Morgan, who could have easily bought the Psalter himself, had he wished. To repay the loan, funds were raised by public subscription with thousands donating. There were collection boxes in museums, contributions from university colleges, even the Labour Government coughed up £7,500. It is fair to say that the Psalter belongs to the nation. On another visit to Irnham, I found the church was closed. But I managed to collar a local man who was walking his dog. I asked him (the man not the dog) if he knew when the church might be open. He expressed surprise that it was closed and said that he would go and fetch Charlie to open it for me. It turned out that Charlie was in fact the churchwarden. A few minutes later this gentleman appeared wielding a large key. He apologised that the church was not looking its best at the moment because of all the cleaning and disinfecting the Church of England was imposing on local parishes due to coronavirus. He also politely asked me to complete the Test and Trace form. He unlocked the massive oak door, and allowed me in after I had added my signature to the register. I wandered around the church, snapping the Psalter and the exquisite Easter Sepulchre, thinking that they are very nice people in Irnham. Although pages from the Psalter are reproduced on the British Library website, I always think it is far better to view the original manuscript, or failing that, the facsimile. To see an example of the latter, I recommend going to St. Andrew’s. Parking is risky in Irnham, but if you can find a space by the roadside, and Charlie has unlocked the church, it will be a most rewarding visit. Back to top

Castle Bytham

There can be few of us who have not seen the great earth mound at Castle Bytham, the remains of the old castle, which has fascinating links to the Norman conquest and the Barons’ wars against King John and Henry III. It was a motte and bailey castle, consisting of the earth mound, the motte on which the keep was built, surrounded by a fenced area for ancillary buildings, the bailey. The castle was constructed sometime before 1086 by Drogo de la Beuvriere, Lord of Holderness in Yorkshire. Drogo fought alongside William the Conqueror when he invaded England in 1066. As his reward, Drogo was granted extensive lands in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, including the manor of Bytham. In the late 1100s, the manor was granted to William de Colvile, and then in 1215 to William de Forz, 3rd Earl of Albermarle, an Anglo- Norman nobleman.

He was actively engaged in the struggles of the Norman barons against King John and King Henry III but changed sides as often as it suited his policy. These struggles were rebellions against these Kings in protest against their tyrannical will, their foreign friends governing the country and oppressive taxation. After King John's death in 1216, de Forz supported Henry III, fighting in the Battle of Lincoln Fair in 1217. His real object was to revive the independent power of the feudal barons, and he made alliances with other rebellious lords. In 1220 de Forz refused to surrender two royal castles of which he was constable. Henry III marched against them and they fell without a blow. In the following year, however, de Forz, in face of further efforts to reduce his power, rose in revolt. In the winter of 1220-21 de Forz fortified the castle at Bytham, and King Henry III laid siege in February 1221 requiring the use of heavy siege weapons. It held out for nearly a fortnight against Henry. After the rebellion was quashed miners were brought in to slight the defences. The manor was returned to the Colviles, who rebuilt and re- occupied the castle until the late 14th century. The castle was clearly highly regarded for John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, chose to raise his children at Bytham including Henry of Bolingbroke, later King Henry IV. In the 15th century it fell into decline and by 1544 was in ruins. The castle was subsequently dismantled for building stone and by 1906 no stonework was visible above ground. Excavations in 1870 revealed a large keep with a great cylindrical tower 60 feet in diameter with curtain walls and outworks including water defences drawn from the neighbouring beck and local springs. The remaining earthworks are in excellent condition and are an impressive sight especially from the road north to Swayfield. The castle is on private land and access to the mound is not really allowed. But there is a bridge over the stream and footpaths surround most of the site giving excellent views. On my last visit there were useful information boards, giving a history of the castle, a map of the earthworks, and an impression of it in its heyday. Parking is on the road alongside, a bit risky perhaps. Altogether, well worth a trip. Back to top

Lost Villages

Known to historians as deserted medieval villages, these were communities that flourished centuries ago but have now disappeared off the face of the Earth. Many were mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086, William the Conqueror’s great survey of England, but are now just empty fields. The extinction of these settlements seemed to have happened in the 14th century and is usually blamed on the Black Death, the plague epidemic that first struck England in 1348, but came back again and again for more than 300 years. Estimates vary, but from a third to a half of the population died. Once it took hold in a small village it went through the inhabitants like wildfire until they were all gone. Historians have advanced other reasons such as climate change, coastal erosion and replacement of arable farming with sheep and cattle raising. More deserted villages have been found in the East Midlands and Eastern England than the rest of the country with over 130 listed on the Lincolnshire Historic Environment Record. Some are close to home: Bowthorpe settlement, south of Manthorpe, Stow near Barholm, Elsthorpe near Edenham and Banthorpe near Braceborough. There are at least 15 in our adjoining county of Rutland. But they are very difficult to find without aerial photography or archaeological investigations. Only rarely are humps and hollows or cropmarks seen on the surface.

There are three lost villages in Rutland in a cluster around the A1, which was the Great North Road: Horn, Hardwick and Pickworth. All that remains of Pickworth are the arch from the south porch of the original church (pictured here) in a private front garden of the newer village and a few vague humps and hollows in a field to the west where sheep now graze. On old maps, the lost village is called either Mockbeggar or Top Pickworth. A golf course and a farm occupy the location of Hardwick lost village. Two interesting alternative reasons have been advanced for their loss. During the 15th century, England was gripped by the Wars of the Roses, the armed conflict between the rival houses of York and Lancaster for the crown of England. In 1460 King Henry VI’s queen Margaret was marching south from Yorkshire with a vast army of northerners and mercenaries after her defeat of the Yorkists at the battle of Wakefield. On their way south to attack London, the Lancastrians wrought fear and great destruction on the towns of Grantham, Stamford and Peterborough, all Yorkist supporting and on the Great North Road. It is possible that the three villages were destroyed by the ravages of this army. In the same conflict, the battle of Losecoat Field in 1470 was fought in or near the area occupied by the villages. According to the information board outside Pickworth Church, the village was described as having no residents by 1491 and advances the idea that it was destroyed following the battle. The same explanation could apply to Hardwick and Horn. Villages on the east coast like Dunwich in Suffolk and Skipsea in Yorkshire are still being lost to coastal erosion. War has claimed Tyneham in Dorset, taken over in the second world war as a tank firing range and training ground for the army. Fortunately, the coronavirus pandemic, which is now hopefully diminishing, has not led to the devastating consequences of the Black Death seven centuries ago. Back to top

Grimsthorpe Castle

We are fortunate to have Grimsthorpe Castle, one of the finest country houses in England, within the boundary of our group of parishes, indeed right on our doorstep. The architecture, the park and gardens, the walks and bike rides, are first-rate. As is the story of the castle, albeit long and convoluted. The castle’s early history is linked with the abbey of Vallis Dei, the Valley of God known as the Vaudey, which stood to the south of the present lake in the castle grounds. The site was granted in 1147 to the Cistercian order by William, Count of Aumale and Earl of York, a major landowner in the north of England. At first the abbey flourished with profits from wool. But by the end of the thirteenth century the abbey had suffered financial difficulties and the number of monks had fallen. The abbey was a victim of the dissolution of the monasteries by King Henry VIII in 1536. An archaeological dig in 1851 revealed the four crossing piers of the chapel.

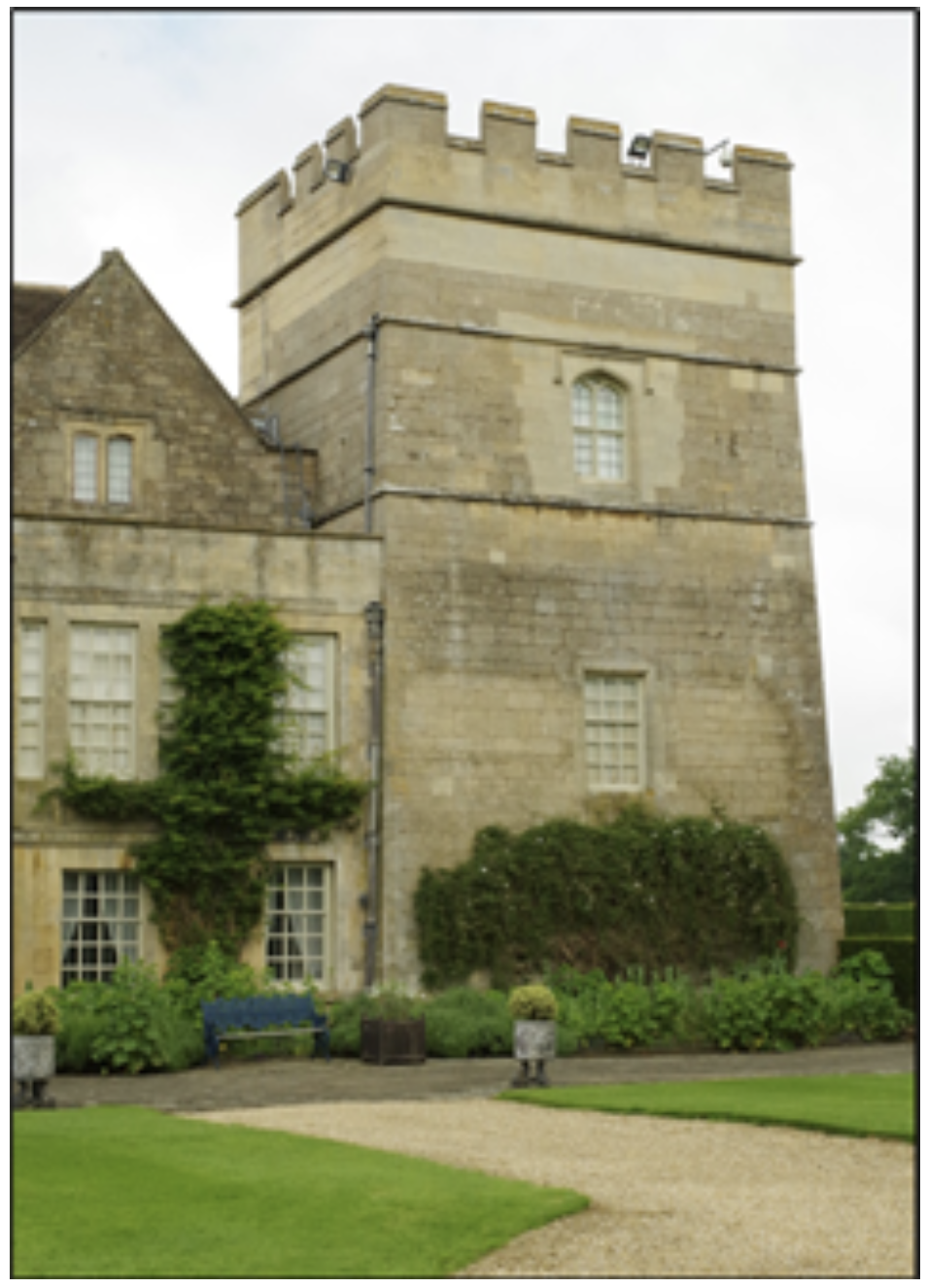

It is likely that the first castle was built by a certain Gilbert de Gant in the 13th century. Gilbert was made Earl of Lincoln in 1216 by Prince Louis of France who claimed the throne of England and considered himself entitled to create earldoms. Gilbert fought against King John in the Baron’s Revolt; an armed insurrection led by Prince Louis. Gilbert was captured and deprived of his estates and title. He died in 1242. Much of the estate eventually passed to Henry, 1st Lord Beaumont, who served in the armies of both Kings Edward I and Edward II. The south east tower of the castle is named King John’s Tower (pictured) and is the earliest part of the castle still standing. In view of Gilbert’s opposition, how it got its name is a bit of a mystery. At some point in the late 15th century the castle was in the hands of Viscount Francis Lovell a close friend and supporter of King Richard III. After Richard was killed at the battle of Bosworth in 1485, Lovell raised rebellion against the new Tudor king, Henry VII. The rebellion ended at the battle of Stoke Field near Newark in 1487 when Henry defeated the rebels and Lovell disappeared, presumed dead. His lands were confiscated by Henry for his part in the rebellion. Grimsthorpe remained in Crown hands until 1516 when it was granted to William Willoughby, 11th Baron Willoughby d’Eresby, on his marriage to Maria de Salinas a lady-in-waiting and friend of Queen Katharine of Aragon, wife of Henry VIII. Dating back to 1313, the Barony of Willoughby d’Eresby is an English peerage which can descend in the female line as well as the male. In March 1520 Maria gave birth to a daughter, Catherine, who was only about six when her father died and she succeeded as 12th Baroness and heiress to Grimsthorpe. She became a ward of the king until 1528 when Henry VIII sold the wardship to his brother-in-law, Charles Brandon 1st Duke of Suffolk. Suffolk's devious plan was for his young son, Henry Brandon Earl of Lincoln, to improve his prospects by marriage to Catherine. But the scheme collapsed in 1533 when Suffolk’s wife died and their son Henry became terminally ill. Ever the opportunist Suffolk, then aged about 50, took the fourteen-year-old Catherine for his fourth wife. In 1541 Henry VIII honoured Suffolk with a royal visit to Grimsthorpe Castle and the Duke spent the previous eighteen months frantically upgrading and extending the Castle. In fact, in 1539, Suffolk was granted the lands of the dissolved Vaudey Abbey the materials of which he clearly pillaged for his new work. He built three small towers and four ranges to form a courtyard, all of which survives. The south west tower is named the Brandon Tower. After Suffolk died in 1545, Catherine’s second marriage was to Richard Bertie. Their grandson, Robert Bertie, became 14th Baron Willoughby d’Eresby and inherited the estate in 1601. He was created Earl of Lindsey by Charles I in 1626 and had the Four Mile Riding laid out in the park. The Riding was an avenue of oaks running from the Castle to the lake and is shown on old maps. His grandson Robert Bertie, third Earl of Lindsey inherited the property in 1666 and undertook the complete rebuilding of Grimsthorpe in the classical style and laid out the gardens. Robert’s son, another Robert, was created Duke of Ancaster and Kesteven by King George I in 1715. This Robert commissioned Sir John Vanbrugh to rebuild the north front of Grimsthorpe in the baroque style to celebrate his elevation. Vanbrugh was the architect of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard, and Grimsthorpe was to be his final masterpiece. The front of the castle was subsequently redesigned and there were plans to complete the other three facings of the castle in the same style, however these were never carried out. The north front was completed in 1730, four years after Vanbrugh’s death. It is probable that after 1726 Nicholas Hawksmoor, another celebrated architect in the baroque style, took over the completion of the work. The end result is a large quadrangular house with a central courtyard, with each side reflecting the different architectural styles employed since building began in the 13th century. The park and gardens consist of 3,000 acres of rolling pastures, lakes and woodland created by the master landscape architect “Capability” Brown. I regard the view from the western range across the park down to the lake on a summer’s day as the finest view in England. The present owner is Jane Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby, 28th Baroness Willoughby d’Eresby, granddaughter of Nancy Astor the first woman MP who died at Grimsthorpe in 1964. Whether you visit to enjoy the park and gardens, hire a bike and go for a ride, go on a tour of the house, enjoy tea and cake in the tea room or admire the architecture, you will not be disappointed. Back to top

The Flodden Plaque

The small village of Tickencote lies in the east of the county of Rutland, two miles north-west of Stamford. The village is mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 with the Countess Judith of Lens, a niece of William the Conqueror, listed as Tenant-in-Chief. From the 17th century the Lordship of the Manor was held by the Wingfield family. The first of that name was John Wingfield who moved into Tickencote Hall in 1602 with his wife Elizabeth. John originated from the Suffolk branch of the family who came from the village of Wingfield in Suffolk. They in turn descended from Sir Henry Wingfield of Letheringham, also in Suffolk. The Tickencote Wingfields were great benefactors of the local church, financing its restoration in 1792.

For such a small village to have a church at all is surprising. What is even more remarkable is that the church is exceptionally fine with superb architectural features. The massive Norman chancel arch is rightly regarded as the finest in England, the stunning rib vault in the chancel is certainly unique in the country and there is a 600 year old wooden recumbent effigy, sadly now showing its age. For these features alone the church is well worth a visit. Easily overlooked amongst these attractions is a small oak plaque on the south wall of the nave. Inset into the plaque is a brass tablet commemorating the death of Sir Anthony, one of the Suffolk Wingfields, who was killed at the battle of Flodden in 1513. The brass tablet reads, in translation from the old northern English: “At Flodden field did bravely fight and die, Of Wingfield sons, the brave Sir Anthony, But death he counted much gain since he, Over the Scot did gain the victory.” The inscription on the oak plaque reads: “The above was given to this church in 1938 by John Parry Wingfield. It was probably first fixed in Letheringham church in Suffolk. The battle was fought on the 9th September 1513”. According to the Church guidebook, the brass tablet was found in a shop in Lowestoft in 1862. The battle of Flodden was fought in Northumberland. King Henry VIII was in France having joined the Holy League formed by Pope Julius II fighting against French territorial ambitions in Europe, leaving the defence of England in the hands of the 70-year-old Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey. King James IV of Scotland was obliged by a mutual defence treaty with the French to invade northern England. He raised an army of 30,000 men including the flower of the Scottish nobility and marched south from Edinburgh crossing the English border at the River Tweed. The Earl of Surrey mobilised 26,000 men at his base at Pontefract Castle and then marched north to Wooler in Northumberland. Surrey was concerned that the Scots might retreat back across the border from their impregnable position on Flodden Edge, a hill 500 feet high. Surrey and his entire army undertook a daring march in foul weather to outflank the Scots and deployed to the north of the Scottish position. The English had cut off King James’s supply line and his retreat to Scotland, leaving him no option but to fight. A bloody battle ensued, with cannon fire, volley after volley of deadly arrows and vicious hand to hand fighting. The Scottish army was eventually destroyed, King James was killed, the last king in Britain to fall in battle, along with twelve earls, fourteen lords, at least one member of every leading Scottish family and 10,000 of her soldiers. The English lost no more than 1500 men. There is a handsome memorial cross, erected in 1910, at the site of the battle with an inscription: “Flodden 1513. To the brave of both nations.”

There is a memorial window in St. Leonard's Church in Middleton, Lancashire, commemorating the archers of Middleton who fought so valiantly under Sir Richard Assheton in Sir Edward Stanley's division of the English army. The window is claimed to be the oldest war memorial in England. Perhaps the Flodden Plaque in Tickencote Church, Rutland, can challenge this assertion? A visit to the battlefield at Flodden is highly recommended. An equal recommendation can be made for Tickencote Church, which has the benefit of being much nearer. Prepare to be amazed by the chancel arch and the rib vaulting, but spare a glance for the Flodden Plaque and spare a thought for those brave men of long ago. Back to top

Hereward the Wake

Hereward is an almost legendary figure on whom there is little reliable and much suspect information. Born around 1035 and died 1072, his epithet “the Wake” means “the watchful” or is derived from Hereward's relationship with the manor of Bourne in Lincolnshire, which from the mid-twelfth century was held by the Wake family. He is the most famous of all the figures who resisted Norman rule and perhaps is best known for raising rebellion against William the Conqueror and fighting a last ditch stand against the Normans in the Isle of Ely. Traditionally it is said that he was the son of Leofric of Bourne and Eadgyth, a descendant of Earl Oslac of Northumberland, and a nephew of Abbot Brand of Peterborough. Hereward was of high social status holding estates at Witham-on-the-Hill and Barholm-with-Stow as a tenant of Peterborough Abbey and lands as a tenant of Crowland Abbey, according to the Domesday Book. Hereward must have committed some severe transgressions in his youth because he was exiled from England at the age of eighteen for disobeying his father and even worse for being declared an outlaw by the Saxon King Edward the Confessor. He went to the continent and found employment as a mercenary in the service of the Count of Flanders. After the Norman Conquest he returned to England in about 1069 and found his family’s lands confiscated by King William and given to the Norman Ivo de Taillebuis. Hereward’s father and brother had been killed and his brother's decapitated head placed on a spike at the entrance to his house. Hereward took a bloody revenge when with just one follower he slaughtered fourteen Normans at a drunken feast and replaced his brother’s head with theirs. After returning briefly to the continent while the heated situation cooled, he came back to England, only to find that his uncle Abbot Brand had been replaced at Peterborough Abbey by a Norman abbot, Turold of Fecamp. The Danes themselves were still trying to conquer England and their King Sweyn with a small army had established a camp on the Isle of Ely, where Hereward joined them. With the aid of the Danes, Hereward and his crew stormed and sacked Peterborough Abbey, claiming that he resented the appointment of the Norman Turold to the house and that he wished to save the Abbey's treasures from the rapacious Normans. Later he must have felt badly let down by his new friends. Sweyn realised that his force was too small and accepted terms from King William. The Danes left Ely, sailed into the River Thames where they stayed for two nights and then sailed back to Denmark. It is said that they even purloined the loot taken from Peterborough. The Isle of Ely is so named because it occupies an area of raised ground which was the largest island in the Cambridgeshire Fens. The isle was only accessible by boat or causeway making the area relatively easy to defend until the waterlogged Fens were drained in the 17th century. Morcar, the former Saxon Earl of Northumbria, had already raised rebellion against the Normans in the north of England and was well supported. But he was unwilling to take too much risk and advanced with his men to Warwick and there submitted to William leaving his companions high and dry. Morcar and a small remaining force made their way to Ely and joined Hereward. Round about 1071, the King was in Normandy but returned to England to deal with the revolt personally. He called out naval and land forces to mount an attack from all directions. Ships blockaded the island on its eastern seaward side, while to the west his army constructed a pontoon bridge to launch an assault across the marshes. William was foiled on three occasions by the superior military skill of Hereward in his attempts to build a causeway across the impassable marshes. However, during William's first attack the weight of the troops on the bridge was so great that the causeway sank and many soldiers drowned. After many attempts the Normans bribed Abbot Thurstan of Ely to reveal a safe path across the marshes, which resulted in Ely at last being taken. Some of Hereward’s men were imprisoned, but some were set free only after hideous mutilation, a practise William often performed on rebels. Morcar was captured and imprisoned for the rest of his life, but Hereward managed to escape into the wild fenland. There are several conflicting accounts of Hereward's fate after his escape from the Isle of Ely. Some say he was reconciled with William the Conqueror, regained his lands and estates, died in his bed and was buried at Crowland. Others that he was killed by a band of Englishmen. Alternatively, he lived for some time as an outlaw in the Fens, but that as he was on the verge of making peace with William, he was set upon and killed by a group of Norman knights. Hereward owes his popularity as an archetypal English hero in the mould of Robin Hood to the publication in English of the “Gesta Herewardi” (The Life of Hereward) in the nineteenth century.

This is an ancient tome originally written in Latin in the 12th century and from which much of our knowledge is gained. And to Charles Kingsley's novel Hereward the Wake: Last of the English, published in 1866 which is largely based upon it, elevating Hereward into one of the most romantic figures of English medieval history. But Hereward lives on. Even more than nine centuries after his demise his name is celebrated in the Hereward Cross Shopping Centre, Peterborough; Hereward Medical Centre, Bourne; Wake House, Bourne; and the Hereward Way, a long-distance footpath from Peterborough to Ely and probably several others. The picture on the previous page is from a “See Britain by Train” poster in the National Railway Museum in York, captioned “Ely Cathedral where Hereward the Wake made his last stand”. As mentioned before, Hereward is a semi-legendary figure with narratives of his life and exploits recounted in many ancient works most with wildly conflicting accounts. As in most histories getting to the truth is not easy. But why let historical accuracy spoil a good story? Even if there is a grain of truth in the written accounts, he was a determined and brave warrior and epitomises the refusal of the English people to be governed by foreigners. That is why he is still popular today. Back to top

Baptist Noel

It is said that the only places to see English medieval sculpture is in our cathedrals and parish churches. This observation is nowhere more true than at the church of St. Peter and St. Paul in Exton, Rutland, which contains nine magnificent monuments, several of which are outstanding. Probably the finest is the huge marble monument to Baptist Noel, 3rd Viscount Campden, on the east wall of the north transept. The grandly named Baptist was a nobleman in Rutland who gained notoriety in the English Civil War as a staunch Royalist who led his band of followers in brutal plundering raids across Rutland and Lincolnshire from bases in Belvoir and Newark castles. In 1611 Baptist was born at Exton Park into the powerful Noel family, son of Edward Noel the 2nd Viscount Campden. In 1632 Baptist married Lady Anne Fielding and then Anne Bourchier in 1638. Sadly, these ladies had short lives and their children all died young. Baptist married his third wife, the Hon. Hester Wotton, in 1639 and they had four daughters and two sons who survived. In 1639 Baptist and his father accompanied King Charles I in the ill- fated war against the Scottish National Covenant who vehemently opposed the King’s attempt to reform the Scottish Church. The King summoned Parliament to provide money to support this war. The so- called Short Parliament only ran for three weeks in April 1640 and was replaced by the Long Parliament in November that year. Baptist, as a Knight of the Shire, was elected to both but, being a Royalist, his association with the latter parliament was brief. Parliament refused to grant funds until its grievances were resolved but the autocratic Charles refused to compromise and the Civil War between them soon broke out. Baptist was commissioned into the Royalist army and was based at Newark castle when he succeeded as 3rd Viscount Campden on the death of his father in March 1643. At the head of his troop known as the “Campdeners”, he plundered the property of his local opponents and frequently imprisoned them. He rose rapidly through the ranks being appointed brigadier of foot and brigadier of horse in July 1643. Both sides fiercely contested Rutland; and Exton Park along with neighbouring Burley Park, the home of the Duke of Buckingham, were confiscated by the Parliamentarian forces. The Campdeners seized Stamford, drove away cattle, and generally became a serious threat. It got so bad that on the 10th April 1643 Oliver Cromwell wrote to Sir John Burgoyne of Potton in Bedfordshire, the chief member of the Bedfordshire Committee, to request troops of horse to resist the raiders. On 19th July 1643 the Campdeners attacked Peterborough with a large force but were repulsed and fell back on Stamford. They were defeated at Burghley House by Cromwell on 24th July. Baptist continued to resist the Parliamentary forces, leading his cavalry troop in daring raids across Rutland and beyond. In late 1645 the war was effectively over and Baptist resigned his field command. By October 1645 he was a prisoner in London. He was released in August 1646 and allowed to return to Rutland. He was fined over £19,000 by Parliament, this massive amount demonstrating the severity of his offences. In May 1648, after long negotiation and with Baptist severely in debt, his fine was discharged on payment of £100. His wife, Hester, died the following year and was buried at Exton on 17th December 1649. Baptist married his fourth wife, Lady Elizabeth Bertie, eldest daughter of Montague Bertie, second earl of Lindsey, on 7th July 1655. They had nine children. After the civil war he was restored to his estates when he laid out geometric areas of woodland, divided by avenues with formal gardens, and a lake close to Exton Park. Baptist died at Exton on 29th October 1682 aged 71 years and was buried on the north side of the church there. His wife Elizabeth survived him by only a few months, dying in July 1683. His monument, squeezed into a space too small to adequately display it, is of white and black marble made by Grinling Gibbons, perhaps better known for his carvings in wood, celebrated as the finest sculptor working in England at the time. It shows Baptist and his fourth wife Elizabeth, flanked by two obelisks, separated by a pedestal. They are standing on a base with reliefs of their children.

The whole monument is on a lower base with a relief showing his third wife Hester and hers, and on the obelisks the first and second wives, two Annes, and their children. Twenty-five figures in all. On the base are two black marble inscriptions, on the left giving brief biographical information on Baptist, while that on the right gives the names of his children by his four wives. On the pedestal between Baptist and Elizabeth is a black marble inscription plate recording that the monument was erected by order of Elizabeth and carried out by her third son, John Noel, in 1686. The monument is topped by a large broken pediment displaying the Campden coat of arms. As was the fashion for the age, all of the figures are depicted in Roman dress. It cost £1,000, the equivalent of over £200,000 today. The monuments in Exton church were restored by the Exton Monuments Restoration Fund between 2000 and 2002. Baptist’s monument cost £49,000 to restore. Opposite Baptist’s monument is another to his son James Noel, who died aged 18 years. It’s smaller but no less well executed. In addition, there are superb replicas of the original funerary and armorial banners of the Noel family hanging above the nave. The church is at the end of a lane just before the village. The lane is narrow so care must be taken in case another car decides to come the other way. Parking is on the verge at the end of the lane. A visit to see the church and the monuments will be a joy. It’s like an art gallery, but free, and well worth a pound or two in the collection box. Editor’s note: According to one historic wealth calculator, the original fine of £19,000 given against Baptist in 1646 was equivalent to the wages for a skilled tradesman for 743 years’ work! Back to top

Clipsham Yew Tree Avenue

In the village of Clipsham in Rutland there is a handsome Hall built in the local limestone and surrounded by parkland. The Hall was originally constructed in 1582 but was drastically rebuilt in 1700 in the classical Doric style of architecture, leaving just one wall from the original structure. There were many additions and further alterations made in the 19th century. The Hall is the hub of the Clipsham Estate which includes the productive limestone quarries and a half mile long carriage drive lined with Yew trees. In the mid-Victorian period, the estate came into the hands of the Handley family. When the purchaser, John Handley MP for Newark, died, he left the property to his nephew William Davenport on the condition that he adopt the additional surname Handley. In 1870 the Estate Head Forester, a Mr Amos Alexander, asked John Davenport-Handley, the Estate owner at the time, if he could enhance the carriage drive by clipping the Yews into different shapes, an art called topiary. Mr Davenport-Handley agreed, providing that each tree was different and paid tribute to events and people of local, national and world interest. However, he would not allow depictions of women, Queen Victoria being the only exception. Family members with their names and years of birth would be depicted in topiary, as would important events in the family such as when David Davenport-Handley went to Dartmouth Royal Naval College in 1930, depicted by an anchor, and when Leslie Davenport- Handley celebrated her ruby wedding anniversary.

Queen Victoria was represented in each of her jubilees. The tops of each tree were made into the shapes of various birds and animals. In 1955 the Avenue was let to the Forestry Commission on a 999-year lease. Experts were brought in to continue the tradition of topiary and they created clippings showing a Spitfire from World War 2, Neil Armstrong as the first man on the moon in 1969, the county of Rutland gaining independence in 1997, a windmill and the initials of Amos Alexander and Sir David Davenport-Handley. And thus, the carriage drive became the celebrated Clipsham Yew Tree Avenue. The result is an avenue unique in this country with free entrance to the public, open every day of the year, complete with car parks, seats, picnic tables and information panels. Topiary is only found in private gardens and never in such numbers as in the Avenue. The trees in the Avenue are over 200 years old, planted in Napoleonic War times. It is deservedly one of the top attractions in Rutland. At the road entrance there are two Copper Beech trees, one on each side of the double gates. Each bears a metal plaque stating that it was planted by Sir David Davenport-Handley on 21st March 1986. Strangely, the one on the left has grown better than the one on the right. The stone-built lodge, built in 1860, also on the left of the gates is grade II listed. It appeared to be empty until a few years ago, I know this because I often took a peek through the windows, but now it seems to have been converted to a private house. At the end of the avenue are a further set of gates from which there is an excellent panorama of the estate parkland with a distant view of the Hall. There is also a not terribly comfortable seat and a useful information board describing the fauna and flora of the Avenue. In 2010 the Forestry Commission announced that it no longer had the funding to continue with the clipping and the trees soon became diseased and overgrown. The patterns on the trees were lost, bank voles chewed up the ground and the Yews deteriorated further. The grass was not cut and large potholes appeared in the car park and approach roads. Despite its increasingly poor condition, visitor numbers to the Avenue remained high. Fortunately, in 2012 a number of local people started to raise serious concerns about the lack of maintenance and the very survival of the Avenue. In 2018, a new charitable trust was formed – the Clipsham Yew Tree Avenue Trust, a group of local people determined to get something done. They estimated that £15,000 to £20,000 would have to be raised each year to maintain and improve the Avenue. With help from local MPs and council leaders, they set about fund-raising and have received several grants. The Trust has contracted with the Forestry Commission to take over the management of the Avenue and a regular program is now in place. The Trust have certainly done a superb job with the Avenue now looking better than ever. Supported by the Friends of Clipsham Yew Tree Avenue, an extra car park has been built, growth behind the Yews has been cut back, the grass has been regularly cut, seats, picnic tables and information boards have been installed, drainage channels cleared and many, but not all, of the potholes on the entrance roads have been filled in. And of course, the topiary is in the process of being restored. That no entrance fee is charged is amazing. A visit is a great experience and is extremely popular. Visitors, with or without granny or dogs, can go for a pleasant walk, take the kids for a noisy run about, have a picnic in good weather, photograph the flora and fauna or just sit and admire the trees and breathe God’s fresh air. But when arriving take care to avoid the occasional pothole, there are still a few remaining to be filled up. Back to top

The Essendine Earthworks

Anyone motoring through Essendine in Rutland cannot fail to have noticed the small and delightful church of St. Mary’s on the corner when leaving the village on the A6121 going towards Bourne. A mixture of Saxon, early Norman and mid-Victorian, the church occupies a substantial plot with a graveyard on the right, a field with many sheep to the front, and an extensive area of earthworks behind. The earthworks, surprisingly, are nearly a thousand years old, starting life as a ringwork and bailey raised in the last half of the 11th century by the Norman invaders. A ringwork was a basic structure consisting of a raised earth rampart surmounted by a palisade fence protected by a surrounding ditch. The bailey was a separate enclosure also with rampart and ditch, either encircling or separated from the ringwork. Soon after the conquest, the Normans were faced with rebellions all over England. In response they built castles to suppress the native Saxon population. In the early years of the occupation, such castles were not massive stone towers but simple defensive earthworks and Essendine could have been one of these. A hundred years later the entire site was redeveloped into a defended manorial estate either by William de Bussey, Lord of Essendine from 1159, or his successor Robert de Vipont.

The completed estate consisted of a central square platform upon which was built a manor house, surrounded by a moat. To the south was a bailey which is still partly occupied by St Mary's Church, taken over as the estate’s chapel. A further enclosure to the north served as a fishpond, an important source of food in the medieval household, and there were additional ponds to the south of the church, although these were filled in during the 19th century. The estate occupied a low-lying site with the moats and ponds fed from the River West Glen that runs north to south on the east of the site. An earth bank separated the estate and the river. The estate passed through the hands of numerous families during the medieval period. In 1296 it was owned by Robert de Clifford, in 1318 it was held by John de Cromwell and from 1336 by the Despenser family. In 1447 it passed to Cecily Duchess of Warwick and thereafter it remained in the hands of the Earls of Warwick until taken into Crown ownership by King Henry VII in 1499. Queen Elizabeth I later granted the estate to Sir William Cecil, the Lord Treasurer. It fell into disrepair someone during the seventeenth century, eventually being dismantled. No remains of any buildings are visible today. The whole site is over 5 acres in extent. In 1951 the site was designated a scheduled ancient monument by Historic England. St. Mary's Church is of late Saxon or Norman origin, itself listed grade II* in 1961, and the structure is excluded from the scheduling of the manorial estate, although the ground beneath the church is included. The modern burial area alongside the church is totally excluded. Access to the earthworks themselves is not possible as the entire area is fenced off and occupies private land used for grazing sheep. At least the landowner, or his flock, do a good job of keeping the earthworks reasonably clear of dense undergrowth allowing their full grandeur to be seen. The only views of the earthworks are obtained from the graveyard at the east end of the church and from the small area alongside the west end. Views of the remains of the fishponds to the north or any views across the river from the east are completely blocked off by a thick line of trees immediately west of the river going north from the parapet of the bridge carrying the A6121. Parking is available on the grassy area alongside the track to the church and is used by members of the congregation attending services. The entrance to the track is from the main A6121 road through the village going towards Bourne, immediately after the bungalows on the left. The entrance is rather abrupt, so care must be taken. But a visit to the church and a close sight of the ancient earthworks is most rewarding and makes taking this very minor risk well worthwhile. Back to top

The Siege of Burghley House

Few will disagree that Burghley House in Stamford is the finest Elizabethan country house in England and richly deserves its fame and its grade 1 listing. Most of the rooms and interiors received make- overs in the 18th century but the exterior largely retains its original period appearance. The magnificent 1,300-acre park surrounding the house was laid out between 1755 and 1780 by the celebrated landscape architect Capability Brown who also built the lake and the Lion Bridge. The house was built between 1555 and 1587 for Sir William Cecil, later 1st Baron Burghley, Lord High Treasurer and Secretary of State to Queen Elizabeth I. Queen Elizabeth was succeeded by King James I (also King James VI of Scotland – son of Mary Queen of Scots) in 1603, followed in turn by his son Charles I in 1625. Charles was a very different monarch to Elizabeth. In religion he was uncompromising, enforcing the High Church form of ritual worship. He believed in the "the Divine Right of Kings", meaning he was above the law and answerable only to God. Rather than cooperate with his Parliaments Charles treated them with contempt and levied taxes without their consent. In early 1642, he tried, unsuccessfully, to arrest five members for treason. This action, and his unyielding attitude to religion and politics enraged Parliament and his subjects who saw his actions as those of an absolute and tyrannical monarch, which soon led to riots breaking out and eventually to civil war. In its early years the war was a series of skirmishes and battles fought locally between local forces. In 1643 the Royalists, who supported the King, were in a strong position in the East Midlands having occupied Newark Castle in December 1642 and Belvoir Castle in January 1643 and large-scale raids were launched into the area from these strongholds. On the 11th April 1643 a raid on Grantham led to a Royalist victory at Ancaster Heath, prompting a southern offensive led by Viscount Baptist Camden. On 19th July, Camden took command of a 1,000 strong force from Belvoir and Newark Castles and assaulted Peterborough, held by the Parliamentarians. The attack was repulsed by Colonel Palgrave commanding a regiment of foot (infantry) from the Wisbech garrison. The Royalists retreated in disarray to Stamford. Palgrave was reinforced by Colonel Oliver Cromwell who arrived from Northamptonshire with seven troops of horse (cavalry) and three companies of foot. Arer a vicious skirmish around Wothorpe House, the Royalists restored to the grounds of Burghley House, held by the Countess of Exeter for the King, and sheltered behind its stone walls. Cromwell suffered no losses in the skirmish but several Royalists were killed or captured. On the 23rd July the Parliamentarians were further reinforced by 4,000 men and 14 cannon from East Anglia. In the pitch dark early the following morning they opened a two-hour bombardment but made no impression on the defenders. The Royalists were offered quarter but they refused.

The fighting then resumed until the afternoon when the heavily outnumbered Royalists finally surrendered. Cromwell took them all prisoner: two Colonels, six Captains, four hundred foot, two hundred horse and all their weapons. Cromwell later sent the Countess of Exeter a portrait of himself by Robert Walker, which still hangs in Burghley House, out of the high regard he felt for the lady. Marching towards Grantham, the Parliamentarians were attacked by four hundred “clubmen” two miles outside Stamford at Great Casterton. Clubmen were local civilians who supported neither side but who just wanted to defend their property and their families from attacks by rapacious armies. The clubmen killed some of the Parliamentarian scouts but then Cromwell sent four troops of horse to drive them off. Fifty clubmen were killed and the rest fled into nearby woods. No siege damage to Burghley House can be seen. The south front may have been destroyed in the bombardment and, as has been suggested by some architectural historians, was rebuilt in its entirety in the late seventeenth century. Further rebuilding took place during the period of the 9th Earl of Exeter’s ownership in the eighteenth century when, guided by Capability Brown, the south front was raised to alter the roof line and to allow bever views of the new parkland he had designed. The south front is a bit difficult to get at (see opposite). The west side of the house is protected by what is known as a ha-ha (pictured below), comprising a 6-foot- deep trench, revetted on the house side with a stone wall. The ha-ha keeps the wandering deer away from the house and garden but unlike a hedge or fence does not interrupt the view. The south end of the ha-ha is hard against a fence and the lake. The south face of the house is also protected by the same fence and lake. Sadly, all this protection prevents close examination and photography of the south side of the house. The siege is a fascinating part of the history of Burghley House but strangely the attack is not mentioned anywhere, neither at Burghley itself nor in its website nor in any of its publicity. Nevertheless, a visit is always rewarding. Although a charge is made for a tour of the house, entrance to the grounds is free. A new car park opened in May 2023 and is also free, at least for the moment. The grounds are wonderful to walk around with many ancient trees particularly oaks, sweet chestnuts and sequoias dotted about, and some stately tall conifers at the west end of the lake. The herds of deer appear to wander at will and are very photogenic, providing they are not approached too closely. It’s all very calm and very peaceful, a far cry from the sounds of cannon fire and conflict from times long ago. Back to top

The Car Dyke

Before rushing off home to defend their capital from invaders in the fifth century AD, the Romans had been very active during their 400-year occupation of this country, particularly in our area. Apart from crushing the native British tribes, they built roads such as Ermine Street and King Street, large townships like Durobrivae west of Peterborough, the Fossedyke canal connecting Lincoln with the River Trent, and Car Dyke, an 85-mile long canal in eastern England. The Car Dyke was built in around AD 125. It runs along the western edge of the Fens from Washingborough, east of Lincoln, to Eye, east of Peterborough. However, archaeologists claim they have found sections of it at Waterbeach, north of Cambridge, suggesting it ran much further east. It is thought that the Car Dyke once linked up with the Fossedyke built around AD 120. If this theory is correct then the Romans possessed a strategic waterway all the way from East Anglia to the north of England. The Car Dyke is one of the largest of the known Roman canals and is an important feature of the Roman landscape in the Fens. Along with their road system and Hadrian’s Wall, it is one of the greatest engineering feats carried out in Britain by the Roman Empire. Excavations on parts of Car Dyke have shown that the water channel, before it became silted, was approximately 40 ft wide at the top and between 7 to 13 ft deep, with sloping sides and a flat bottom. The purpose for which Car Dyke was built is hotly debated among historians. Archaeologists have found boats with cargoes of pottery, coal and grain of the Roman era and dressed stone of the medieval period, leading them to think that Car Dyke was used for transport. The canal may have been also used for military purposes, to carry food and supplies from East Anglia to their advancing armies in the north, the main cargoes being corn and salted meat for food, wool for uniforms and leather for tents and shields. Another suggestion is that its primary purpose was to serve as a drain to control and divert flood waters, acting as a catchwater drain intercepting runoff from the higher ground to the west. Car Dyke may well have been built for agricultural drainage purposes so as to produce more fertile land for crops. The emperor Hadrian visited Britain in about AD 120 and the sections dating from this period may be associated with his plan to settle the Fens. Major works to drain the Fens to improve the land for agriculture took place in the seventeenth century and evidence has been found of improvements to Car Dyke dating to that era overlying construction from the Roman period, thus incorporating the canal into local drainage schemes. Whether constructed for transport, military defences, drainage or agriculture, Car Dyke still remains an impressive work of civil engineering and is designated a scheduled ancient monument. Fortunately, it is marked on larger scale OS maps and there are many places where it may still be seen. In my younger and fitter days, I traced Car Dyke east of the B1177 and B1394 between the north of Bourne and the east of Sleaford at Heckington, Horbling, Sempringham, Dowsby and Dunsby. In some of these places the canal is just a shallow weed choked ditch, most unimpressive.

In other locations it has been maintained much better, the banks have been cleared and the weeds removed from the water. A few places have very fine brick arched bridges carrying the narrow fen roads. In our locality a good place to see the canal is in Bourne. The A151 past Tesco goes over a bridge across Car Dyke. A better place is the far end of the car park at Lidl supermarket from where there is an excellent view of the canal going south (pictured above). At Thurlby church the canal passes between the churchyard and the A15. There is in fact a footpath from Thurlby east of the A15 all the way to Bourne on the east side of Car Dyke, which I have yet to try. On its way south and east, Car Dyke runs along the north side of the Paston Parkway to the north of Peterborough. In 2011 a new road designated the A16 was built which branches off from the Parkway and goes north towards Crowland and Spalding. As the new road had to cross Car Dyke, the initial plan was to run the canal through a concrete culvert. But as Car Dyke and its verges is a scheduled ancient monument, English Heritage would have none of it and insisted on a bridge. The plans were changed to cross the waterway with a 240 ft span “bow stringed” arch bridge, increasing the £80 million cost of the road by another £3 million. I do not recommend going to the bridge site to see the canal. The A16 here is a busy road carrying fast moving traffic and one must park on the verge of the road beyond the crash barriers which can be extremely hazardous. There is no lay-by. A great shame, as the views of the canal here are excellent. Whatever your opinion of the Romans, either as a civilising influence or as cruel military occupiers, you cannot deny that they were brilliant engineers and builders. That Car Dyke is still recognisable, and in fact still in use at least in part, after nearly 2,000 years is testimony to this fact. Along with the Roman roads mentioned above, it is still worth going to see, as it is a valuable addition to the local history of our area. Back to top

The Manners Monument or a Mystery at Uffington