The Life & Times of Richard Bertie

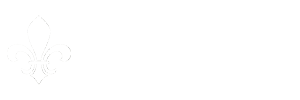

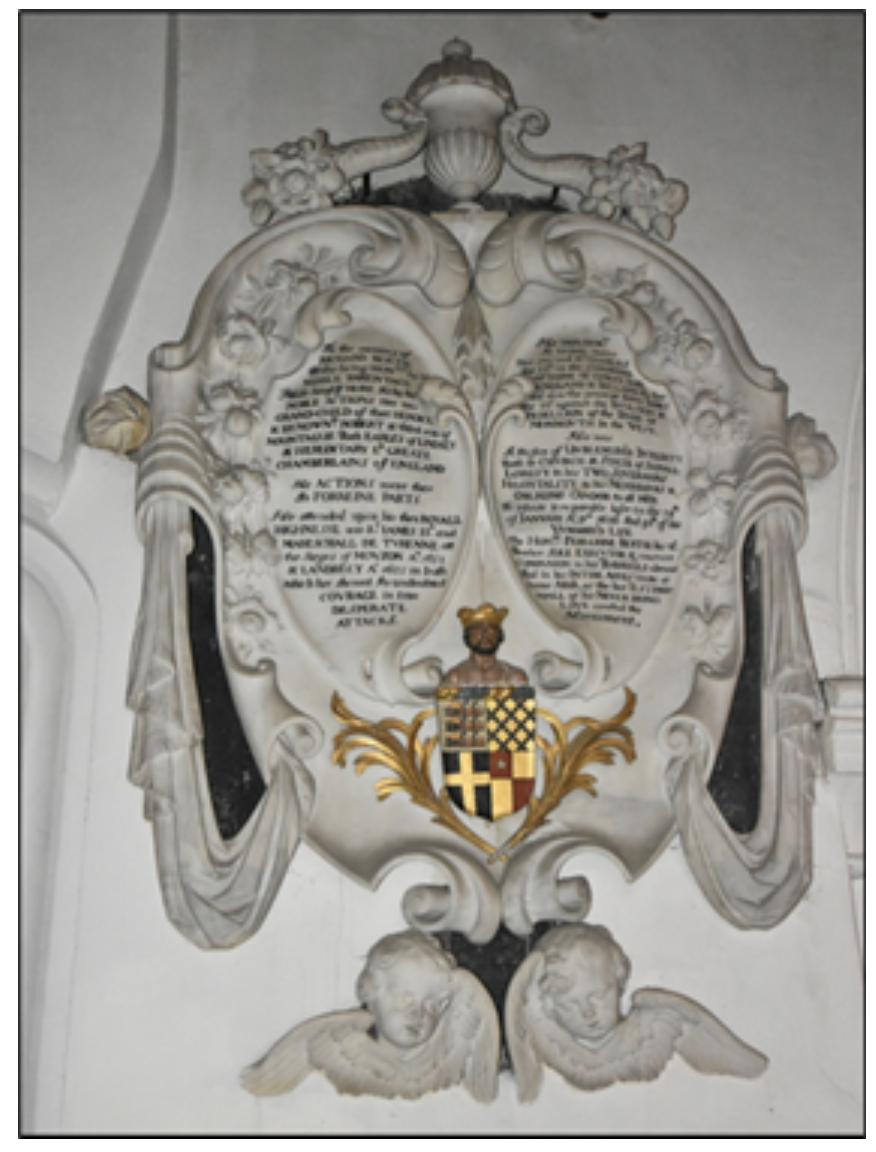

Amongst the many superb memorials in Edenham Church is a particularly fine white marble tablet dedicated to Richard Bertie who was born in 1635 and passed on in 1686. Tucked away in a dark corner at the east end of the north aisle of the church, the visitor must really hunt around to find it. But the search is rewarding. Coincidentally placed next to the black marble memorial to his grandfather, Richard’s memorial is superbly carved, and contains extensive details of his life in the flowery language of the 17th century. We learn that he was indeed of illustrious parentage, being the grandson of the first Earl of Lindsey, of Grimsthorpe Castle, who was killed at the Battle of Edgehill in 1642, and the son of Montagu, 2nd Earl of Lindsey. Both father and grandfather were Knights of the Garter, the highest order of knighthood in the kingdom, founded in 1348, the oldest in the world.

And both were hereditary Lords Great Chamberlain of England, the Officer of State to whom the Sovereign entrusts the custody and control of the Palace of Westminster, the responsibility for the organisation of the State opening of Parliament, and who plays a major role in a Coronation. To escape the vindictiveness of Oliver Cromwell’s republic, Richard and his elder brother Peregrine were sent out of the country by their father in 1649. Richard travelled throughout Europe before joining the Duke of York (later King James II), serving in the French army under Marshall Turenne during the Thirty Years War. The Thirty Years war of 1618 to 1648 was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history, caused mainly by the Protestant Reformation in the Germanic states and those who opposed it. The Franco-Spanish war was part of this wider conflict and Richard distinguished himself in the Siege of Mouzon in eastern France in 1653. In the midst of the Franco-Spanish War, the nobility, the law courts (“Parlements”), as well as much of the French population, rose in revolt against the government of the young King Louis XIV in what was known as “the Fronde”. Again, Richard won acclaim in the capture of the fortress of Landrecies in 1655 during this uprising. Our man returned to England at the Restoration of King Charles II in 1660 and briefly pursued a political career. He was a commissioner for assessment of taxation in Lincolnshire, was appointed a justice of the peace in Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire and was returned as Member of Parliament for Woodstock in Oxfordshire in March 1685. When King Charles II died on 6th February 1685, he left no legitimate issue. But despite being a Catholic, his younger brother James acceded peacefully to the throne as King James II. However, James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, eldest illegitimate son of Charles II, had other ideas. He was vehemently opposed to a Catholic King and in 1685 led a group of like-minded Protestants in an armed invasion known as the Monmouth Rebellion in the west of England with the object of toppling the King. But Monmouth was opposed by James who had a standing army of nearly 20,000 men. Richard Bertie was part of this force as a Captain commanding a troop of horse. The Royal army easily defeated Monmouth on 6th July 1685, at the Battle of Sedgemoor, the last pitched battle fought on English soil. Monmouth himself was captured hiding in a ditch disguised as a shepherd. Tried and found guilty of High Treason, Monmouth was sentenced to death by beheading. However, Monmouth's execution was hideously bungled. The executioner took five strokes with the axe and even then the head was not completely severed and had to be finished off with a knife. Monmouth was interred, along with many other victims of execution, in the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula in the Tower of London. King James's reaction to the Monmouth rebellion was to plan the increase of the standing army and the appointment of loyal and experienced Roman Catholic officers. But Richard and his younger half-brother Captain Henry Bertie did not support his measures and as a result were deprived of their commissions in December 1685. Richard died on 19th January 1686 and was buried at Edenham. He never married. Edenham Church houses the monuments to the Berties, Lords Willoughby de Eresby and later Dukes of Ancaster, all of Grimsthorpe Castle, some of them huge and very ornate, but a series larger than that in any other Lincolnshire church. Richard was a politician, a magistrate and a soldier, and thoroughly deserves his place amongst these worthies. Back to top

The Wilsthorpe Effigy

In April of 2021 the editor of the Three Towers in his wisdom published an article of mine entitled “Recumbent Effigies” describing the several stone figures of knights in armour, and sometimes their ladies, to be found in churches in our area. Since then, more information has come to light regarding the effigy at St. Faith’s church at Wilsthorpe (pictured). St. Faith’s is one of the smallest churches in South Lincolnshire. It was built in 1715 as a replacement for an earlier church, underwent extensive changes in the 1860s, and is a mixture of classical and gothic styles. The church is in a delightful rural spot, backing onto fields in this very quiet village.

The effigy is to the left of the altar, beyond the rail, in a dark corner of the church up against the north and east walls. In fact, it just fits between the altar rail and the east wall. In such a small church there is probably nowhere else to put it. Its position restricts close viewing and photography but that is a minor consideration. The legs are crossed, the right foot is missing, the other rests on what appears to be a faithful dog. The shield on his left arm is hard up against the wall. His head rests on a pillow and the right arm is across the chest grasping the top of his shield. He has two swords, one beneath the shield the other on his right hip although this may be a dagger. Sadly, much of the detail on the shield and on his belt is worn, presumably lost to the centuries. It is interesting that Sir Nikolaus Pevsner in his “Buildings of England – Lincolnshire” (2nd edition) claims that the effigy with the arms of the Wake family must be a 17th century fake. He says “the crossing of the legs is improbably done, and the surcoat and its carved pattern is also improbable. The way the hand lies instead of holding the shield has no parallel. Finally, although all this tends to convey a date about 1300, the lavish belt and the moustache would spell 1375 or so”. Pevsner does not think much of the church either, using terms such as “cruel alterations” in the 1862 rebuilding, and “the ridiculous shingled broach-spire”. The Shell Guide to Lincolnshire by Thorold and Yates (published 1965) is not a fan of the church either, describing the pinnacled exterior as “comic”. The church is listed Grade II*, the description of the building describes the effigy as “late 13th century, recut”, as does Historic England. It is fortunate that the church authorities are unmoved by any criticism of their church or effigy. They have written and displayed useful information, propped up on the organ, describing the effigy as “a stone figure of a knight believed to be circa 1340 bearing a shield with the arms of the Wake family to which the famous Hereward is supposed to have belonged. An inscription in English around the hem of his tunic reads: “Peace is better than war”. Sadly, none of this detail could be seen as the effigy is badly worn. There is even graffiti scratched on his person. On a visit to Barholm Church in July 2011 I met the then vicar, Carolyn Kennedy, who was also vicar of St. Faith’s. She told me that the Heraldry Society have investigated the effigy and have pronounced that it dates from 1340 to 1350 and is in the style of tournament armour. The Wake family of Lincolnshire claim descent from Hereward the Wake (died 1072) who gained fame by raising rebellion against William the Conqueror. Hereward had a daughter named Turfrida by his second wife, Alftruda. Descending from Alftruda and at the end of a long and tortuous genealogical path comes John (1268 – 1300), created the first Lord Wake in 1295. He served King Edward I, campaigning in Gascony between 1288 and 1297 and against the Scots from 1297 to 1300. He fought in the battle of Falkirk in 1298. John’s son Thomas, 2nd Lord Wake (1297 – 1349), also fought against the Scots for King Edward II. Another branch of the Wake family includes Sir Hugh Wake (1202-1241) who fought in Brittany with King Henry III and died on Crusade in the Holy Land fighting the Saracens with Simon de Montfort. His grandson, another Thomas (1280-1347), was present in France with King Edward III, where he fought at Crecy in 1346, and at the siege of Calais in 1347, where he died. There must be other family members of a martial disposition. Members of the Wake family of Lincolnshire were also Lords of the Manor of Bourne, and of Deeping. It is far too much to expect that the effigy is one of these warriors. And if so, how come he is commemorated in a tiny church in deepest Lincolnshire? Due to his age, he must have been moved from another church, perhaps the forerunner of St. Faith’s at Wilsthorpe. The identity remains an enduring mystery. Or possibly a fake, or even re-cut. Surely this is part of the attraction. A trip to Wilsthorpe is highly recommended, and then the visitor can form his or her own opinion.

Back to topThe Protector’s Widow

King Charles I remains the only English King in history to be tried and executed for treason, a judicial murder which caused outrage and horror throughout the British Isles and Europe. Charles was beheaded in 1649 aper the defeat of his armies by Parliamentarian forces in the English Civil War. Parliament’s army was commanded by Oliver Cromwell, arguably the most capable soldier in England at the time. He was also a Member of Parliament and a radical politician, bitterly opposed to the King, and it was largely at his instigation that Charles was put on trial. Realising that the country needed a head of state, Parliament declared that Oliver Cromwell be the Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland, a King in all but name. But away from politics and the battlefield he was a dedicated family man. In 1620 he married Elizabeth Bourchier, daughter of a London merchant. Theirs was long and stable marriage which produced nine children of whom eight survived until adulthood. Cromwell died at Whitehall on 3rd September 1658. A violent storm wracked England on the night of his death, said by his enemies to be the Devil carrying away his soul. He was buried in Westminster Abbey following an elaborate funeral service. His son Richard, known as “Tumbledown Dick”, took on the duties of Lord Protector, but he was not the man his father was. In 1659 the Protectorate was dissolved, the army took over the government and the country became a military dictatorship. Parliament was rudely known as The Rump, and was a shadow of its former self. Elizabeth Cromwell, known as the Lady Protectress, was well- provided for at her husband’s death and given an annuity and lodgings in St James’s in London. When the Protectorate fell, the ruling Council of O?cers urged the Rump Parliament to treat her generously. In spring 1660, on the eve of the Restoration of the Monarchy, she left London, but was accused of purloining jewels and other goods belonging to the royal family. She strongly denied the charge. Elizabeth went to live in the Manor House in Northborough, Cambridgeshire, with her son-in-law John Claypole, where she spent her last years in quiet retirement. Aper a period of declining health, she died in November 1665 and was buried in Northborough church. The Manor House had provided a comfortable residence for the Protector’s widow. It is at the south end of the village, a small stone-built fortified hall of two storeys under a gabled roof. A gatehouse stands by the road with a magnificent arched entrance and added on to the west is a large, early seventeenth century barn into which a row of circular gun ports was cut during the Civil War. (Pictured). There appears to be dispute over who originally built the Manor House. Either by Geo?rey De La Mare in the early 14th century and renovated and extended in the 17th, or built between 1333 and 1336 by William de Eyton - the Master Mason and Architect of Litchfield Cathedral. The Manor House was owned in the 17th century by the Claypole family. John Claypole, was born on 21st August 1625, the eldest son of John Claypole and his wife Mary. John Claypole the younger was a Parliamentary soldier, politician, and great friend of Oliver Cromwell. He married Elizabeth, Oliver’s second and favourite daughter, at Holy Trinity Church, Ely, on 13th January 1646. John first appeared in arms for Parliament at the siege of Newark in the winter of 1645–6, and rose to become a colonel of a regiment in July 1651.

On 11th August 1651 he received a commission from the Council of State to raise a troop of horse in Northamptonshire to oppose the march of Charles II into England. At the Restoration of the Monarchy John returned to Northborough. But John had financial difficulties and had to sell the Manor in 1681 to a Lord Fitzwilliam. John died on 26th June 1688. John and his wife Elizabeth seem to have spent most of their married life in London rather than Cambridgeshire. Elizabeth sadly died in August 1658. Their children, three sons and a daughter, all died young. St. Andrew’s in Northborough is along Church Lane which turns o? the main road between the Manor House and the Packhorse pub. The church has a late 12th to early 13th century nave and a very large south chantry chapel known as the Claypole Chapel. The chapel contains the graves of some of the Claypole family. John and Elizabeth were both buried in London, but at least two of their children were laid to rest in the chapel. Elizabeth, widow of Oliver Cromwell, is buried in a vaulted charnel house beneath the chapel. Although no contemporary monument survives, a large broken, and repaired, floor slab is traditionally said to mark her grave. The Cromwell Association have set up an inscribed tablet in her memory on the east wall. Unfortunately, I have always found St. Andrew’s church locked thus preventing a visit to the Claypole chapel, and the old Manor House is a private dwelling so it must be admired from the outside. Northborough was on the main road into Peterborough until February 1989 when the A15 Glinton bypass opened, but the road through the village is still a bit busy, so street parking is risky. However, the landlord at the Packhorse pub, close to the Manor House, will allow use of his car park if politely asked. Visiting these places in Northborough is not always easy, but like most things in life, putting in a bit of e?ort makes the experience most rewarding.

Back to topIn Praise of Tracery

Among the many architectural splendours to be enjoyed in our Gothic cathedrals and parish churches, the decorative stonework called tracery in the windows is one that is frequently overlooked but still worthy of admiration. The Gothic style of church architecture was imported from France in the late 12th century and soon became the true English style. English Gothic came aper the fortress-like Norman style. Norman architecture has thick walls, massive columns and tiny round-headed windows. Gothic was a revolution, with pointed arches, rib vaulting to the ceiling, thinner walls with flying buttresses to support them, and large windows containing beautiful patterns of tracery, all leading to much more graceful buildings. The first design used in the Gothic style is known as Early English. Windows in Early English were Lancets, tall, narrow windows each with a sharp pointed arch at its top containing plain or stained glass. It acquired the "lancet" name from its resemblance to a lance. There is no tracery. Lancets are open seen together in groups of three or more, sometimes the central lancet is taller than the rest.

West Window - Perpendicular

These grouped lancet windows gave way in the mid-13th century to larger and wider windows. Larger windows obviously meant a larger area of glass, which needed supporting against the pressure of wind. Which then led to window tracery. The pointed arch feature of the Gothic style created a space below the peak of the arch which is filled with decorative stonework. Below the arch are mullions, vertical ribs of stone dividing the window into two or more vertical window “lights” or panels of glass. If the window was particularly tall then horizontal ribs called transoms were added, giving more support to the glass and creating more lights. The outside of the ribs themselves are moulded or shaped and the ribs create an intricate pattern over the whole window. The term tracery probably derives from the tracing floors on which the complex patterns of windows were laid out. These patterns were full size. Tracings were taken, then wooden templates were cut from the tracings and passed direct to the mason who carved the stone ribs. Plate Tracery is the earliest form, where the area of stone was greater than the glass. The “plate” of stone was simply pierced to create small areas where glass was inserted. In the 13th century plate tracery began to give way to Bar Tracery, where the area of glass was greater than the area of stone. The simplest form of bar tracery was “Y tracery”, where the thin stone mullion separating two window lights branched into two sections in the shape of a letter Y. Another simple form is Intersecting Tracery where the mullions curved to the arch head, crossing over each other in the process. As Gothic architecture developed, windows became much wider, and there might be three or more lights, separated by stone mullions, with increasingly complex tracery patterns above the lights. The fascinating subject of Tracery uses a wealth of technical terms, beloved of architectural historians in an attempt to describe the patterns and place each one into a named category. For instance, Geometric tracery has circles, trefoils and quatrefoils below the peak of the arch above the stone mullions. Curvilinear or flowing tracery involves more complex shapes based on ogee curves. The final phase of Gothic was the Perpendicular style of architecture of the late 14th century which has mullions crossed at intervals by horizontal transoms. This pattern is open called Panel Tracery or Rectilinear Tracery.

East Window Cusped curvilinear tracery C14 Restored

Patterns of tracery are complicated and it is frequently impossible to tell to which category a window belongs. Besides, quite a lot of windows do not seem to fit these neat categories. There also seems a dispute about which pattern of tracery is in which category. A visitor to a church is not necessarily an architectural historian and the layman need not be concerned with all the complicated categories of tracery that I have been at pains to describe. A visitor travelling around our area will see many examples of beautiful window tracery. A good example of grouped lancets is on the chancel wall at St. Mary, Essendine. There is plate tracery at St. Mary, Clipsham, in the east wall of the north aisle and also in the spire bell-openings. The east window of St. Martin, Barholm uses intersecting tracery. At another St. Mary, in Swinstead, the west tower is Early English with Y tracery in the bell openings and the east window has four lights with curvilinear or flowing tracery. I think the east window is the one of the most stunning I have seen. But the finest example of Geometric tracery must be the great east window in the Angel Choir at Lincoln Cathedral. At 59 feet high it has eight lights and seven circles above, all filled with gorgeous stained glass. If an opportunity occurs, it has to be seen. Not quite so grand but still worth seeing is the late 13th century east window at St. Andrew, Folkingham, with four lights and three circles. There are several windows at St. Michael, Edenham, of the Perpendicular style, particularly the east and west windows of five lights. And a very fine west window at Folkingham which has a castellated transom, resembling small battlements. As has been seen, tracery thrives in our local churches. And knowledge of terminology and category names, although there are a scattering in this article, is not needed to appreciate its magnificence. Best thing to do is just enjoy the architecture and revel in its beauty. No need to get technical.

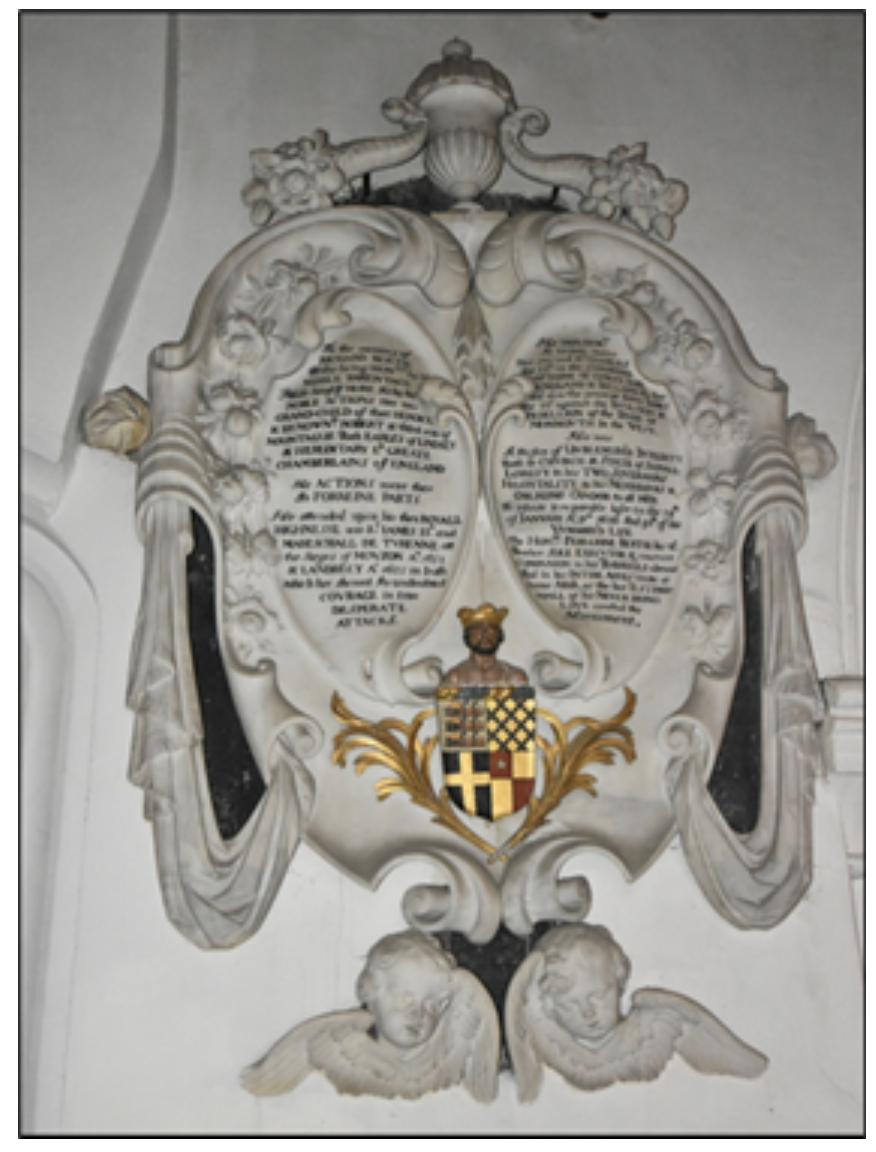

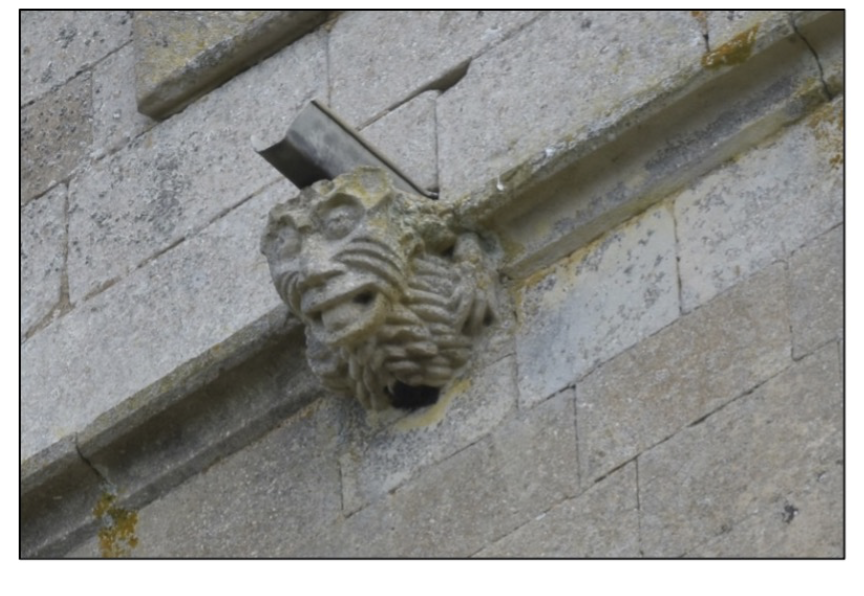

Back to topGargoyles, Grotesques and Miscellaneous Carvings

Gargoyles are elaborate carvings in the shape of fearsome and frightening beasts frequently found on medieval churches and designed to carry rainwater away from the walls from its mouth or from a short pipe projecting from its mouth. Grotesques are carvings in a similar vein that serve no architectural or structural purpose whatsoever and are purely decorative. These figures are often thought of as protection from evil spirits and as reminders of the separation of the earth from the divine. Architectural historians and scholars have documented the history and origin of the names. For instance, the term “gargoyle” comes from the French word “gargouille,” that means throat but sounds like “gargle”, hinting at the function of these figures. “Grotesque” originates from the fascination with the Roman empire which led in the late 1400s to the excavation of ancient caves adorned with murals depicting human and animal forms. The Italian word “grottesca” means cave which in turn evolved into the term “grotesque.” A “chimera” is a type of grotesque depicting a mythical combination of multiple animals, sometimes including humans.

The most common reason why grotesques and gargoyles are often used in medieval architecture is that the grotesques were “apotropaic”, meaning to ward off evil. It’s often said that grotesques are concentrated on the north sides of buildings, the sunless side from which demons would be expected to attack. Not true, grotesques are evenly distributed all round many Gothic churches. Some kinds of grotesque carving are, shall we say, rather risqué. These are surprisingly common in medieval churches. The two commonest theories are that they are apotropaic, or that they are warnings against the sin of lust. But could it be that the masons were entertaining themselves, having a laugh? Was it a fashion amongst them? Or perhaps they had carved grotesques on other buildings and decided to include them where they were currently working. In the 13th century there was a monk called Bernard who was famous for building big abbeys and churches mainly in the west country. Even he admitted that even he didn't know why they were made. St. John the Baptist Baston St. Mary, Swinstead There are gargoyles and grotesques on several of our local churches. St. John the Baptist at Baston has a fine west tower in the Perpendicular style with a moulded string course just below the battlements. Gargoyles are mounted just below this course. The odd thing here is that rainwater chutes project immediately above the gargoyle, almost resting on their heads. St. Andrew at Irnham has a similar arrangement with rainwater channels above the carving. St. Michael and all Angels at Edenham also has a handsome Perpendicular west tower with a frieze just below the battlements with excellent grotesques. But in my view the finest grotesques are found at the top of the tower at St. Mary, Swinstead. There are four of them, positioned at each corner of the tower. A bit of lichen grows on them and there is some erosion. But despite the wear and tear, they are in remarkably good condition. Not only that but as the tower is a bit short, they can be more easily viewed.

And St. Mary has a decent size car park! Strangely, “Buildings of England” by Sir Nikolaus Pevsner describes these grotesques as gargoyles, when there is no provision for rainwater drainage. There are many other types of carving, not necessarily grotesque, on our parish churches that should not be ignored. For example, a short frieze of small human heads above the south buttress on the west wall at the base of the tower at St. Mary, Clipsham. All around the very top of the tower at St Stephen, Careby, just below the start of the roof, are several human heads in a variety of expressions that are almost grotesque. St. Michael Langtoft has a similar row of heads at the top of the tower. Nor should carvings in the inside of churches be ignored. Not gargoyles or grotesques but still worth mentioning. For instance, at St. Andrew Witham on the Hill there are very fine carvings on the ends of the pews in the chancel and small but excellent stone heads in the spandrels of the arches in the nave. Several churches have carved angels, with wings spread wide, projecting from the wall-plates at the bottom of a wooden ceiling, often called an angel roof. St. Martin, Barholm is a particularly superb example. Far more attractive than gargoyles. The trouble with gargoyles, grotesques and most interior carvings is that they are usually high up, and as we rarely tend to look upwards, they are often not noticed. Which is a shame because they are well worth looking at. The good thing is that very few churches are entirely bereft of such works of art, except perhaps the smaller churches. So, the best advice when visiting any church is simple: look up.

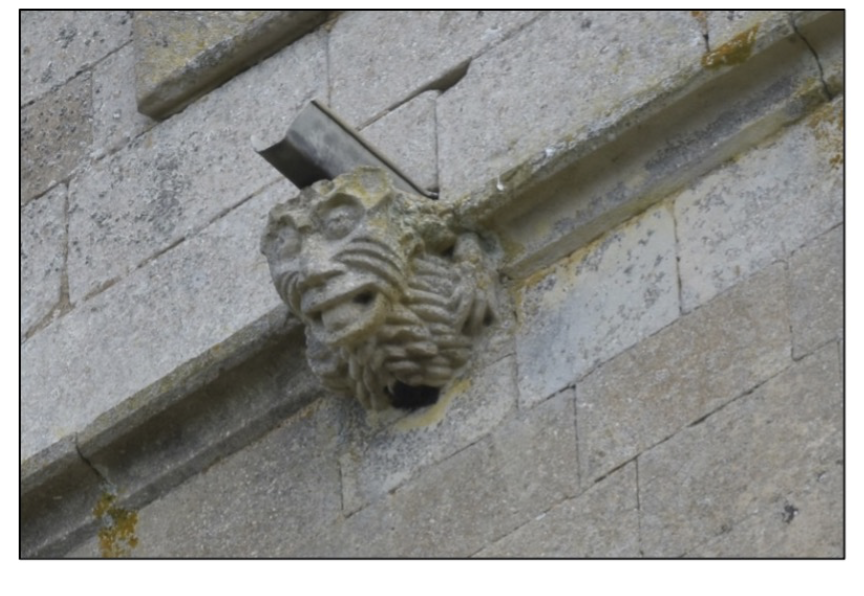

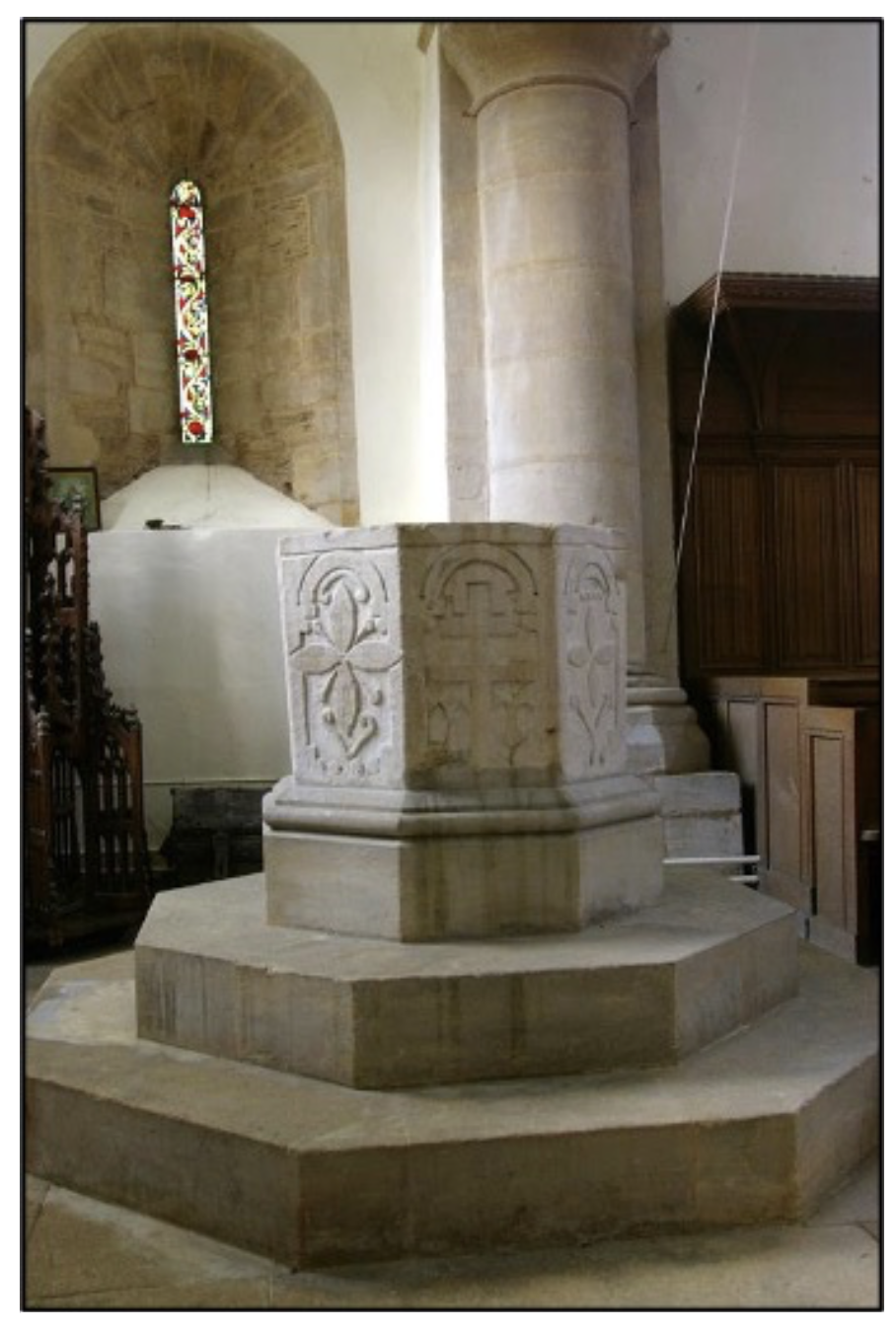

Back to topThe Three Fonts

At a risk of stating the obvious, all Christians know that a font is a piece of sculpted stone found in a church for holding Holy water for use in the baptism ritual, which represents admission to the Church of England. The service of baptism involves water being poured into the bowl in the font, blessed by the vicar, then poured or sprinkled onto the recipient’s head, or used to make the sign of the cross on the forehead. Baptism for babies and young children takes place in a service called a Christening. There is no reason that an adult cannot be baptised. Some churches will perform total immersion as the act of baptism for adults.

Fonts have existed for many centuries. In fact, the oldest ones are over 1,000 years old, shallow pools cut into the soft tufa rock in the floor of baptismal chapels in the Roman catacombs. In England, fonts come in many shapes and sizes and are often made by local craftsmen, with decoration ranging from non- existent to elaborate. Late Saxon and early Norman fonts are often built in a simple tub shape, while other variations have the bowl supported on four corner pillars or a single central column. Eight-sided fonts were common from the 13th century and the norm for the 14th century. This is of religious significance for in Genesis, the world was created in seven days. The “eighth day” is the day after the completion of creation and is also the day of Christ's resurrection. Each of the sides of the font could be elaborately carved with religious symbols, figures of saints, green man variants and heraldic shields. Fonts would have been paid for by the parishioners, and so the richness of their decoration was determined by the funds available and the prevailing architectural fashions of the time. Some of the more extravagant have elaborate multi-tiered covers, raised for use via ropes or chains and pulleys. Fonts are often placed at or near the entrance to a church's nave to remind the congregation, or visitors to the church, of their own baptism as they enter the church to pray, or just look around, since the rite of baptism served as their initiation into the Church.

But they do tend to get moved around with church alterations, often finishing up near the west end. Witham on the Hill I have never seen fonts in different churches that are the same. There must be no hard and fast rules for fonts. The fonts in each of the three churches in our benefice are all different, as the photographs show. At St. Michaels and all Angels in Edenham is a large drum-shaped font without a stem. Around the drum are shafts carrying unusually two- lobed arches. The font is carved out of one piece of stone and is possibly late 1th century. It has been moved around several times and its present position is a result of filling the nave with pews in the middle of the 19th century.

According to Rex Needle, a local historian, it is currently tucked away in a corner and crammed in by pews and other seating. St. Andrew Witham on the Hill has an octagonal font of about 1660 sitting on a two-tiered octagonal 19th century base. It has carvings to all eight sides consisting of chevrons, foliage and a cross. Pevsner in his “Buildings of England – Lincolnshire” casts doubt on its age but offers no alternative. But he does describe St. Andrew’s as “a strange, alas, over restored, church.” There appears to be a dispute concerning the font at St. Mary, Swinstead. Whereas a notice in the church says it is the same age as the church building, which is early 13th century, the Historic England official listing says all fittings are 19th century including the early 14th century style font. Fonts may be a smaller architectural feature of a church compared to, say, a great west window or a spire, but a font is a living part of a church which plays a role of greater religious significance than the others. That is their attraction. That and their variety, sculpture, carvings, and antiquity. It is always worth taking a good look at the font when visiting a church. You will find it very rewarding.

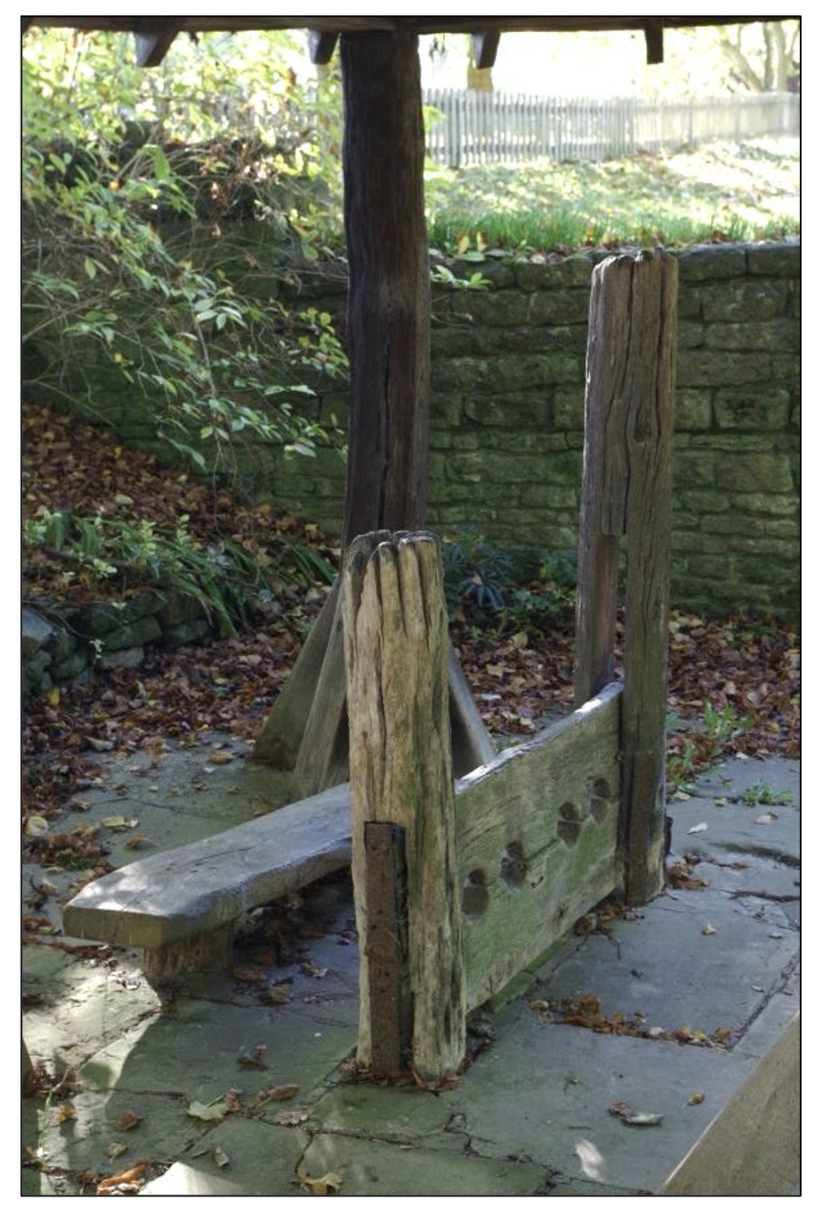

Back to topThe Old Stocks

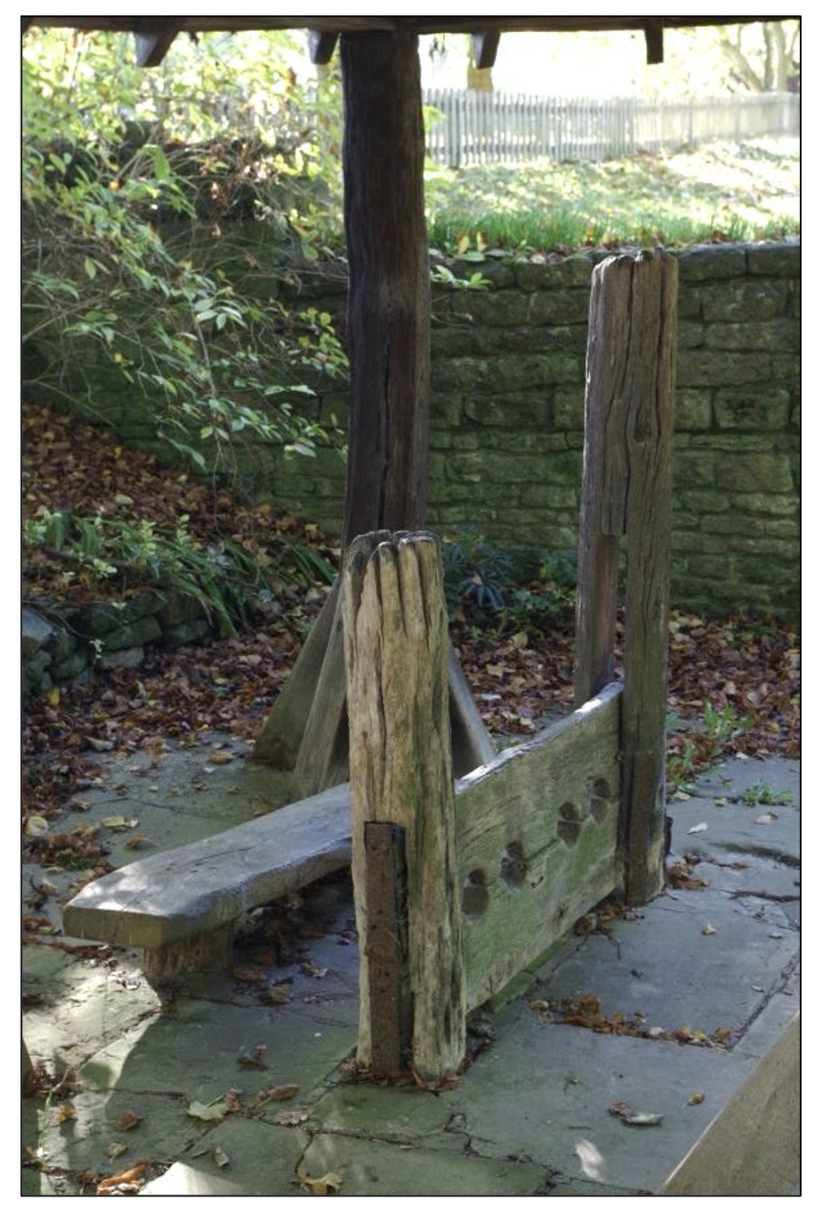

Witham on the Hill is blessed with many fine attractions among which are the old school, the church, the green, the pub and the old stocks, to name just a few. Historic England has judged the stocks to be a historic building, listed Grade II. The stocks are next to a post box and a phone box. The phone box is also listed Grade II. All are on the edge of the green with an adjoining convenient lay-by for parking. Historic England, a government body, maintains the National Heritage List for England, an official, up to date register of all nationally protected historic buildings and sites. Witham on the Hill has twelve listed buildings, Manthorpe by comparison has only one: the bridge.

Thus, the stocks are a protected building, with dire penalties for interference, as is the telephone box. The official listing reads: “The Village Stocks and Whipping Post under the canopy are Grade II listed. They date from the 17th century but were altered in the 0th century. The structures are of timber, with a conical Collyweston slate canopy roof. The stocks have upper and lower boards with four apertures which are set between two posts, one post is taller, presumably a whipping post. The 0th century canopy is supported on four timber posts”. The wording must mean that the stocks comprising the two boards set between the two posts and doubtless the bench seat behind, are at least 300 years older than the conical roof with its four supporting posts. The whole is enclosed on three sides by a stone wall which bears plaques to commemorate awards to the parish council.

Stocks are not to be confused with a pillory. Stocks just retain the ankles, whereas a pillory holds the neck and wrists forcing the sufferer to stand up with a bent back. Either device was used to punish drunkenness, theft and other petty transgressions. Miscreants were also pelted with rotten fruit, bad eggs and other unspeakable items by the working people some of whom were victims of their crimes. They have been used in parts of Europe for more than 1000 years, possibly much longer in Asia, and as far back as ancient Greece. In England the Statute of Labourers was a law created in 1351 by Parliament in the reign of King Edward III. A clause in the statute prescribed the use of the stocks for "unruly artisans" and required that every town and village erect a set of stocks. The statute was enacted in response to a scarcity of labour caused by the Black Death. The epidemic wiped out at least a third of the population leading those left over to demand higher wages causing a loss of income to the landed gentry. The statute prohibited workers requesting, or landowners offering, higher wages. The 1351 statute was repealed in 1863 along with many other statutes from 135 to 1685 which were deemed to be no longer necessary. However, some sources indicate that the stocks have never been formally abolished in England. Their last known use was in June 187 at Newbury in Berkshire when one Mark Tuck was fixed in the stocks for four hours for drunkenness and disorderly conduct. All I can find out about the history of the stocks in Witham on the Hill is two old photographs of the stocks, dated 190 and 1954. The Historic England official listing says that they are 17th century. But to comply with the 1351 act there must have been an earlier set and the 17th century stocks are a replacement. It would be interesting to know where they were originally sited, how often they were put to their intended use and what happened to them when the 1351 act was repealed. The official listing also says that they were altered or restored in the 20th century. It is possible that the stocks were rescued, restored, and placed in the specially built enclave and the conical roof supported on four posts were erected over them to protect the stocks from the worst of the weather. It is this arrangement that we see today. My two old photographs also show this arrangement, which means that the enclave must be over a century old. All that is missing is the extensive growth of trees on the edge of the green. The photographs also show that the walls of the enclave were sloped, whereas now they are stepped. Sadly, there are gaps in my information about the old stocks, which is unfortunate because they must have a fascinating history. So I am reduced to speculation, or, if you prefer, guesswork. Whether records exist to support or contradict my guesswork is more guesswork. All I can be definite about is that the stocks are well worth a visit and a close look whether or not you are bothered about their history. Mention must be made that the Old Stocks has been fenced off for some months and that there are no notices telling visitors the purpose of the fencing. I refer readers to the June 05 issue of The Three Towers, containing the Witham on the Hill Parish Meeting Chairman’s annual report of 1th May. In summary it says that a concerned resident was worried that the posts supporting the roof might collapse, and raised the matter with the Clerk, who thought the SKDC should investigate. The responsibility for the Old Stocks maintenance has been a cloudy issue for many years but the Parish Council hope that SKDC will carry out some remedial work in the near future.

The villages features these medieval stocks and whipping post which were erected in the 17th century. The first photo below was taken circa 1920 by Ashby Swift of Bourne and the second shot was by an unknown cameraman in 1954. Standing under a canopy of Collyweston Slates which is a fissile limestone from Jurassic period, it is named after the village which lies at the centre of the area where the slate is quarried.

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, swearing or being drunk could get you in a lot of trouble. In fact, it could see you whipped up against a post or locked into a stock by your feet while locals would throw rotten food and stones at you as public humiliation and entertainment were integral aspects of justice at the time.

In Lincolnshire, many of the locations where these punishments were handed out are still intact today and owe their existence to a law passed in 1351 that made it a requirement for every township to provide and maintain a set of stocks.

The pain and embarrassment one would feel being punished for petty crimes in this way made stocks a successful deterrent to many.

Thankfully, the gruesome punishments were phased out in the 18th century and it is thought that the last time the stocks were used in the UK was in 1872 in Newcastle Emlyn.

The National Directory of Village Lock-ups has an entry in the section Stocks, Pillories and Whipping Posts and identifies those that either still remain or were in place in Lincolnshire with the directory referencing other stocks and whipping posts existing or having existed in Alvingham, Cleethorpes, Folkingham, Swineshead, Scrivelsby, Pinchbeck, and Threekingham. Back to top

Monastic Houses

In our modern secular world, the idea that men and women would voluntarily withdraw from society to live in seclusion under strict religious vows, and reject the rewards, comforts and pleasures of normal life, is a concept almost impossible to grasp. Yet for almost a thousand years, up to the 16th century, thousands of men and women became monks and nuns, and did exactly that. And all for faith in God. Their faith must have been very strong, far stronger than we can imagine. Monks lived in monasteries, abbeys, priories, preceptories and friaries, which were sets of buildings comprising a chapel or church, living quarters, kitchens and refectories. A convent or nunnery is the equivalent for women.

Preceptories are monasteries which belonged to the military monastic orders, such as the Knights Templar, founded during the 1th century crusades to the Holy Land. Friars originally lived among poor people to whom they preached and on whom were dependent for support. Thus, they were called monks without a church. Friaries where they could live were only established in the 13th century. Monks and nuns followed several di?erent religious orders, each with a basis in the Roman Catholic faith. These orders di?ered mainly in the details of their religious observation and how strictly they applied their rules. The major orders in England were the Benedictines, Cistercians and the Carthusians. Friars belonged to the orders of Dominicans, Franciscans and Augustinians. There were over 100 monastic houses in Lincolnshire each following their respective orders, with at least twelve examples in our local area and another five in Stamford alone, three of which were Friaries. There was the Greyfriars, a Franciscan friary, the Blackfriars was a Dominican Friary, and the Austin (Augustinian) Friary. This latter site was first occupied by a small house of Friars of the Sack, an order suppressed in 1317. Their land was eventually granted to the Austin Friars. The first monastery in England was founded by Augustine in Canterbury in 598. Augustine had been sent to England by Pope Gregory to convert the pagan Anglo-Saxons to the Christian faith. Many more monasteries followed. However, the English monasteries were devastated by the Viking raids of the 9th century. Yet King Alfred the Great defeated the Vikings and revived the monastic movement by founding new houses in Somerset. Their numbers increased rapidly up to the 16th century when King Henry VIII ordered their dissolution. In addition to a life of work, prayer and study, monks and nuns fed the poor, ran hospitals where they helped the sick, and provided hospitality for pilgrims and travellers. Monasteries established schools, preserved learning and created libraries. The monks were by far the best-educated members of society, open they were the only educated members of society. Monks laboriously copied ancient texts and created new versions, open with beautiful hand painted illustrations called illuminated manuscripts. Examples are the Luttrell Psalter probably created in Irnham by scribes from Lincoln in 130, the Lindisfarne Gospels of about 700, produced on Lindisfarne o? the coast of Northumberland and the 1th century Winchester Bible held in the Cathedral. These manuscripts are justly famous throughout the world. By the 16th century over 850 religious houses existed in England and Wales. Many were rich and held vast estates. In 1534 King Henry VIII broke with Papal authority by the Act of Supremacy, making him and his successors, the Supreme Head of the Church in England replacing the Pope. Between 1536 and 1541 Henry dissolved Catholic monasteries and convents in England, Wales and Ireland and helped himself to their wealth. A few of the abbey churches near centres of population survived as cathedrals or parish churches, but most of the others were demolished. The remains of the buildings were used by local people as a source of building material.

Monasteries did not return to England until the late 18th century. At the dissolution of the monasteries, Peterborough Cathedral survived, along with Abbeys at Bourne, Crowland and Thorney, where the remains of the churches were allowed to continue as Parish Churches. Nothing exists of the remainder. In Stamford, some of the buildings at St. Leonards Priory (pictured above) still exist, as does the splendid gatehouse of Greyfriars. Witham Preceptory, near South Witham, was a Knights Templar house but nothing remains. Temple Bruer, north of Sleaford, was also a Preceptory, and its tower remains as a rare survival of this military order (pictured here). Peterborough Cathedral, founded as a monastery in 655, was one of the first centres of Christianity in Eastern England. It was destroyed by Vikings and re-founded as a Benedictine Abbey in 966. The cathedral building itself was started in 1118. The magnificent ruins of Crowland Abbey, also a Benedictine House, was founded in the 8th Century, ransacked by the Danes in 870, restored, then destroyed by fire in 1091, rebuilt, then destroyed again by an earthquake in 1118. The Abbey was re-built, but su?ered another fire in 1143 and was besieged by Parliamentary forces in 1643 during the English Civil War. The North Aisle of the Abbey is used as the Parish church today. St. Leonard’s Priory met its demise in the dissolution of the monasteries in 1538. The nave of the Priory church was used as a barn up to the 19th century when the Marquess of Exeter restored all the remaining buildings. The monks and nuns of medieval times were undoubtedly saintly people in all that they did. They were gifted builders and talented artists and have been called the social workers of medieval times. Monastic life may seem bizarre to 1st century people but at least the monks left us with a wonderful legacy and should not be judged by 1st century standards. Back to top

The Six Bells Public House

History

The current Six Bells pub in Witham-on-the-Hill was built in 1908 to replace the Black Dog Pub which was closed down by the local squire in the early 20th century because it was too close to the estate stables. The new pub was intentionally built on the edge of the village, and its license was transferred to its new location in 1908. The current building is Grade II listed and was designed by architect A. N. Prentice.

From Black Dog to Six Bells

- The Black Dog was the original village pub, located opposite the gates of Witham Hall.

- In the early 20th century, the squire, Walter Fenwick, closed the Black Dog.

- The Six Bells was built at the end of the village to keep its patrons (the grooms from the stables) away from the temptation of the estate.

- The pub's license was officially transferred to the new building in 1908.

The Six Bells is now an independent family business. A village pub with five bedrooms, a south Lincolnshire institution and has a restaurant serving locally sourced, seasonal dishes - seven days a week.

In 2004, the Six Bells were awarded the coveted Bib Gourmand from MICHELIN Guide. Recognition that was received for twelve consecutive years through to 2015 - for good cooking and good value.

In 2021, Lauren and James returned from the Queens Head to work alongside Ben, Phil, Jim and Sharon - reducing the group to a single location, as it began.

Since then, the Bells' south-facing terrace has been weatherproofed with a timber and glass canopy and in March 2023 MICHELIN's Bib Gourmand award returned with The Six Bells being one of twenty new recipients. In February 2024 they retained the Bib as one of 127 in the UK & Ireland that year. Back to top

St. Andrew's Church

The parish church is dedicated to Saint Andrew. The tower and steeple were re-built in a medieval revival style by the Stamford architect George Portwood in 1737–38. A very useful information page is here, containing history, photographs and other miscellaneous items.

- 12th Century: The church has its origins in this period, with early Norman architecture visible in the south aisle and porch.

- 15th Century: Much of the church's current structure was built during this century.

- 1736: The original tower collapsed, an event local legend attributes to a bell-ringing session where the ringers had taken a break at a nearby inn.

- 1738: The tower was rebuilt by architect George Portwood, who also installed a new clock.

- 1874: The church was restored.

- 1912: Further restoration took place, which included the installation of the oak rood screen.

- 1994: The clock installed in 1738 was restored by Derick Brown.

Architectural and notable features

- Norman architecture: Elements from the 12th century include the south aisle and the arch and doorway of the south porch.

- Tower and spire: Rebuilt in 1738 and topped with distinctive ornamental urns.

- Clock: The church has had a clock for over 400 years. The current clock was installed in 1862.

- Rood screen: An oak rood screen from 1912 is a notable interior feature.

- West front: Features a large five-light west window.

- South porch: An elegant semi-circular arch with an image niche above. Back to top

The Parish Hall

This was the former school with the school house being located next door. https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1240074?section=official-list-entry gives details of both buildings.

White’s Directory 1872 has “The present school and master’s house were built in 1847. The master teaches 30 free scholars, and has also a yearly rent-charge of £4 out of Rag Marsh, near Spalding, left by one Thompson”.

In 1930 Kelly’s Directory had “The old school room, erected in 1847, is now used as a reading room, as well as for technical instruction and parish meetings”.

Squared rock faced ashlar with smooth ashlar quoins and dressings, slate roofs with stone coped gables and crested ridge tiles To the school is a gabled C13 style bellcote. The school is single storey, 4 bay front, with plinth, stepped buttresses and inscribed eaves cornice "Train up a child, in the way he should go, when he is old, he will not depart from it". 4 paired cast iron latticed and bordered windows with cusped ogee ashlar heads. Back to top

The Old School House

The house is T plan of 2 storey, 3 bay front, the left hand bay is advanced and separately gabled.

Central planked door, set in a chamfered pointed surround and gabled with angle buttresses, above a blank trefoil, flanked by 3 light windows.

To the first floor a single 2 light window. All windows have chamfered mullions, cornices, cast iron latticed bordered casements. To the right a square date panel inscribed AD 1847 in Roman numerals. Back to top

Witham Hall Preparatory school

The village has a co-educational preparatory school, Witham Hall, which marked its 60th year in 2019. The hall is a Grade II listed building, dating from c1730 but has been extended several times.

The hall was once owned by descendants of Archdeacon Robert Johnson, the founder of Oakham and Uppingham Schools, including Lieutenant-General William Augustus Johnson MP.

The nearest state primary school is on Creeton Road in Little Bytham and Secondary schools are located in Bourne. Back to top

Stocks are not to be confused with a pillory. Stocks just retain the ankles, whereas a pillory holds the neck and wrists forcing the sufferer to stand up with a bent back. Either device was used to punish drunkenness, theft and other petty transgressions. Miscreants were also pelted with rotten fruit, bad eggs and other unspeakable items by the working people some of whom were victims of their crimes. They have been used in parts of Europe for more than 1000 years, possibly much longer in Asia, and as far back as ancient Greece. In England the Statute of Labourers was a law created in 1351 by Parliament in the reign of King Edward III. A clause in the statute prescribed the use of the stocks for "unruly artisans" and required that every town and village erect a set of stocks. The statute was enacted in response to a scarcity of labour caused by the Black Death. The epidemic wiped out at least a third of the population leading those left over to demand higher wages causing a loss of income to the landed gentry. The statute prohibited workers requesting, or landowners offering, higher wages. The 1351 statute was repealed in 1863 along with many other statutes from 135 to 1685 which were deemed to be no longer necessary. However, some sources indicate that the stocks have never been formally abolished in England. Their last known use was in June 187 at Newbury in Berkshire when one Mark Tuck was fixed in the stocks for four hours for drunkenness and disorderly conduct. All I can find out about the history of the stocks in Witham on the Hill is two old photographs of the stocks, dated 190 and 1954. The Historic England official listing says that they are 17th century. But to comply with the 1351 act there must have been an earlier set and the 17th century stocks are a replacement. It would be interesting to know where they were originally sited, how often they were put to their intended use and what happened to them when the 1351 act was repealed. The official listing also says that they were altered or restored in the 20th century. It is possible that the stocks were rescued, restored, and placed in the specially built enclave and the conical roof supported on four posts were erected over them to protect the stocks from the worst of the weather. It is this arrangement that we see today. My two old photographs also show this arrangement, which means that the enclave must be over a century old. All that is missing is the extensive growth of trees on the edge of the green. The photographs also show that the walls of the enclave were sloped, whereas now they are stepped. Sadly, there are gaps in my information about the old stocks, which is unfortunate because they must have a fascinating history. So I am reduced to speculation, or, if you prefer, guesswork. Whether records exist to support or contradict my guesswork is more guesswork. All I can be definite about is that the stocks are well worth a visit and a close look whether or not you are bothered about their history. Mention must be made that the Old Stocks has been fenced off for some months and that there are no notices telling visitors the purpose of the fencing. I refer readers to the June 05 issue of The Three Towers, containing the Witham on the Hill Parish Meeting Chairman’s annual report of 1th May. In summary it says that a concerned resident was worried that the posts supporting the roof might collapse, and raised the matter with the Clerk, who thought the SKDC should investigate. The responsibility for the Old Stocks maintenance has been a cloudy issue for many years but the Parish Council hope that SKDC will carry out some remedial work in the near future.

Stocks are not to be confused with a pillory. Stocks just retain the ankles, whereas a pillory holds the neck and wrists forcing the sufferer to stand up with a bent back. Either device was used to punish drunkenness, theft and other petty transgressions. Miscreants were also pelted with rotten fruit, bad eggs and other unspeakable items by the working people some of whom were victims of their crimes. They have been used in parts of Europe for more than 1000 years, possibly much longer in Asia, and as far back as ancient Greece. In England the Statute of Labourers was a law created in 1351 by Parliament in the reign of King Edward III. A clause in the statute prescribed the use of the stocks for "unruly artisans" and required that every town and village erect a set of stocks. The statute was enacted in response to a scarcity of labour caused by the Black Death. The epidemic wiped out at least a third of the population leading those left over to demand higher wages causing a loss of income to the landed gentry. The statute prohibited workers requesting, or landowners offering, higher wages. The 1351 statute was repealed in 1863 along with many other statutes from 135 to 1685 which were deemed to be no longer necessary. However, some sources indicate that the stocks have never been formally abolished in England. Their last known use was in June 187 at Newbury in Berkshire when one Mark Tuck was fixed in the stocks for four hours for drunkenness and disorderly conduct. All I can find out about the history of the stocks in Witham on the Hill is two old photographs of the stocks, dated 190 and 1954. The Historic England official listing says that they are 17th century. But to comply with the 1351 act there must have been an earlier set and the 17th century stocks are a replacement. It would be interesting to know where they were originally sited, how often they were put to their intended use and what happened to them when the 1351 act was repealed. The official listing also says that they were altered or restored in the 20th century. It is possible that the stocks were rescued, restored, and placed in the specially built enclave and the conical roof supported on four posts were erected over them to protect the stocks from the worst of the weather. It is this arrangement that we see today. My two old photographs also show this arrangement, which means that the enclave must be over a century old. All that is missing is the extensive growth of trees on the edge of the green. The photographs also show that the walls of the enclave were sloped, whereas now they are stepped. Sadly, there are gaps in my information about the old stocks, which is unfortunate because they must have a fascinating history. So I am reduced to speculation, or, if you prefer, guesswork. Whether records exist to support or contradict my guesswork is more guesswork. All I can be definite about is that the stocks are well worth a visit and a close look whether or not you are bothered about their history. Mention must be made that the Old Stocks has been fenced off for some months and that there are no notices telling visitors the purpose of the fencing. I refer readers to the June 05 issue of The Three Towers, containing the Witham on the Hill Parish Meeting Chairman’s annual report of 1th May. In summary it says that a concerned resident was worried that the posts supporting the roof might collapse, and raised the matter with the Clerk, who thought the SKDC should investigate. The responsibility for the Old Stocks maintenance has been a cloudy issue for many years but the Parish Council hope that SKDC will carry out some remedial work in the near future.